Politics and the Art of Commemoration

By Meredeth Turshen

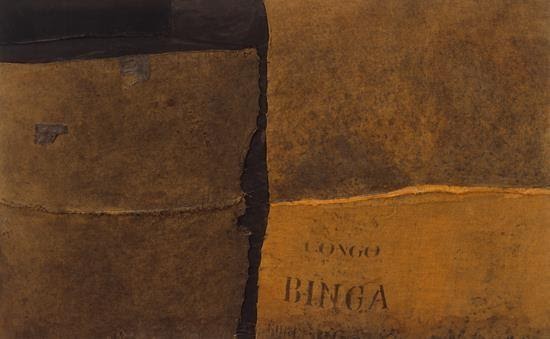

Alberto Burri’s burlap collage, ‘Congo Binga.’ is one of the sacchi (sacks) series exhibited in the retrospective of his work at the Guggenheim Museum in New York (October 9, 2015–January 6, 2016). ‘Congo Binga’ is neither the most imaginative nor the most lyrical of Burri’s sacchi. It does, however, speak eloquently of Italian, African and colonial history.

According to Emily Braun, curator of the exhibition and author of the show’s catalogue, Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting, this painting (reproduced below) was created in 1961 to commemorate thirteen Italian airmen murdered in the chaos of Congolese power struggles that followed independence from Belgium. This account of the work’s origins can be traced to a review of an exhibit of Burri’s work in 1963 at the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, which owns the canvas.

The massacre occurred in mid-November 1961 in Kindu, a town in South Kivu, an eastern province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo that sits just above the copper-rich province of Katanga. ONUC, the United Nations Operation in the Congo, sent the Italians there to deliver supplies to a UN unit of Malaysian troops. ONUC had been established in 1960 to ensure the orderly withdrawal of Belgian forces and to assist the new government in maintaining law and order. Congolese soldiers loyal to Antoine Gizenga, who supported Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first Prime Minister (assassinated on January 17, 1961 in Lubumbashi), apparently mistook the Italians for parachutists fighting with Moïse Tshombe, leader of Katanga’s movement to secede from the Congo.

The scraps of burlap are arranged in quadrants to create a central cross. The patch on the lower right is stamped Congo Binga, the name of a plantation town on a tributary of the Congo River in Equateur Province, some 530 miles northwest of Kindu, where the murders took place. How ironic that a sack from a Congo plantation, the sort of work site where millions of Africans had died at the hands of Belgian colonists, should be used to memorialize thirteen Italian pilots.

Binga plantation belonged to the Lever palm oil monopoly. Jules Marchal, writing about colonial exploitation in Congo, notes that the war years, 1940-45, were the apogee of forced labour on such plantations. The Belgian Congo concluded an agreement with London to supply palm oil, which was at the top of their list of necessary raw materials to produce cooking oil, soap, margarine and cosmetics. To harvest the palm nuts, African workers had to scale trees 50 feet in height; the men were expected to cut fruit and supply 150 crates of it monthly, each crate weighing 77 pounds. They were paid derisory sums for this arduous and dangerous work; even the Belgians admitted that the men were underpaid. Cutters were also compelled to cultivate certain crops (cotton, foodstuffs, palm trees); the work would have fallen heavily on women’s shoulders. Failure to meet the quotas was punished with prison sentences, and in prison the chicotte (a rawhide whip) was still in use in 1959. There is no record of Alberto Burri studying Congolese history and no evidence that he was aware of the brutal story behind Congo Binga.

Alberto Burri (1915-1995) dropped out of school in 1935 to enlist in Benito Mussolini’s campaign to expand the Italian empire in Africa (Italian campaigns of colonial expansion include Asab 1869, Massawa 1885, Somalia 1888, Eritrea 1890, Libya 1894, and Ethiopia 1936). Mussolini was the dictatorial leader of the National Fascist Party and Prime Minister of Italy from 1922 to 1943. After his military service, Burri returned to Italy to study medicine and then enlisted to fight as a frontline soldier in Ethiopia, a ruthless campaign that illegally used mustard gas and phosgene and claimed the lives of three-quarters of a million Ethiopians by the end of the Second World War – an estimated 7 percent of the population. After completing his medical degree, Burri went on to fight in the 102nd Black Shirt Battalion’s invasion of Albania (which had been annexed by Italy in 1939) and to serve as a medic in the Axis campaign in North Africa. The British captured Burri in Tunisia in May 1943. Mussolini was deposed on 25 July 1943 and executed by Italian partisans in the village of Giulino di Mezzegra in northern Italy on 28 April 1945. Following his capture Burri was turned over to the Americans, who shipped him to a Prisoner of War camp in Hereford, Texas. There he took advantage of arts and crafts classes and learned to paint. The Americans urged the imprisoned Italians to sign a pledge of allegiance to the Allies, but Burri was one of some 900 officers who refused to change sides. He was repatriated in 1946.

There is no account of how a burlap sack from Binga came into Burri’s hands. He usually obtained his materials from a mill in his hometown Città di Castello, a city located in the province of Umbria. In 1960, the Binga plantation would have been producing palm oil, coffee, cocoa and rubber — perhaps a sack of Binga coffee beans made its way to Rome. Mobutu Sese Soko, the military dictator and President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (which he renamed Zaïre) from 1965 to 1997, acquired the site following his ‘Zairianization’ of foreign enterprises in 1974. Binga was one of fourteen locations that made up CELZA (Cultures et élévages du Zaïre). The plantation was still productive in January 1999, during the Second Congo War, when Jean-Pierre Bemba (leader of the Mouvement pour la libération du Congo) and General James Kazini (a Ugandan army officer who served as commander of the Uganda People’s Defense Force from 2001 to 2003) organized a large operation to confiscate tons of coffee beans. This is an example of the stripping of Congo assets by Uganda and Rwanda. Binga plantation was all but defunct by the time its current owner acquired it in 2004; he is an American named Elwyn Blattner who heads the Groupe Blattner Elwyn, a vast enterprise of palm oil, rubber and forestry businesses based in Kinshasa, the capital city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

On his return to Italy Burri renounced his medical profession for painting and moved to Rome where avant-gardists like Enrico Prampolini of the fascist Futurist school were urging artists to embrace non-art materials. This suited Burri who had never been to art school and had no formal training as a painter; initially he recycled discarded burlap sacks as canvases. Burri’s fame rose rapidly and he became a major figure in post-war art in Europe, the United States and elsewhere, but he always remained aloof from the art market.

In 1955 he married the American dancer and choreographer Minsa Craig (sister-in-law to Studs Terkel, the popular American oral historian whose progressive political views came to the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee led by the anti-communist crusading Senator Joseph McCarthy). The couple divided their time between the United States and Italy.

How ironic that a sack from a Congo plantation, the sort of work site where millions of Africans had died at the hands of Belgian colonists, should be used to memorialize thirteen Italian pilots.

In the late 1950s Burri shifted from canvases composed of stitched sacks to works that used materials fabricated for housing and office blocks, which were critical to rebuilding the post-war economic infrastructure of Italy. Examples are cheaply manufactured wood veneer, industrial plastics, sheet metal and Celotex insulation board; even the colours of these materials were prefabricated. Through this use of construction materials Burri’s later art is close to architecture, according to James Johnson Sweeney, former director of the Guggenheim Museum and an early collector and promoter of Burri’s work. Architecture had played a seminal role in the advancement of fascist ideology in Italy: throughout the fascist era architecture was employed as a rhetorical device and became the preferred vehicle for launching fascist propaganda. The solidity of architectural materials and the Brobdingnagian proportions of the new buildings exemplified and amplified fascist beliefs. Mussolini’s massive construction campaign to modernize and nationalize transportation and communication networks necessitated the design and erection of buildings that used models not seen before in Italy.

Materiality is central to Burri’s art, and critics have speculated on the meaning of his use of an oxy-acetylene torch to destroy the woods and plastics that were the surfaces of his later canvases. Sweeney was the first to articulate references in Burri’s sacchi to death and destruction, romanticising the artist’s background as a medical doctor caring for troops in North Africa (a curious evocation considering that Italy was part of the Axis and that more than 30,000 Americans died fighting there in World War Two). Sweeney’s reading of Burri underscores the contrast of war-torn Europe with a relatively unscathed America, which lost lives but did not suffer the damage inflicted by Allied air and ground forces on the Continent.

Jennifer Blessing writes that despite Burri’s cool public stance, the sacchi are examples of the Expressionism widely practiced in post-war Europe – called Art Informel in Europe and Abstract Expressionism in the United States. Emily Braun rejects the characterization of Burri’s sacchi as informel, saying that Art Informel became a catchall in the 1950s for gestural and matter painting (Art Brut, Tachisme). “It positioned itself against the School of Paris, the rationalism of hard-edged geometric abstraction and illustrative Soviet realism.” Braun maintains that Burri owed a debt to futurist abstraction, but did not consider himself an Informel artist.

Burri claimed that only the formal demands of construction dictated his use of materials. “If I don’t have one material, I use another. It is all the same,” he said in 1976. “I choose to use poor materials to prove that they could still be useful. The poorness of a medium is not a symbol: it is a device for painting.” Jaimey Hamilton names this statement a defiant negation of any social or psychological meaning that had been or could be read into his artwork and method. Perhaps this position, in which Burri denies the significance of his choices and refuses to attribute deeper meaning to the literal and figurative substance of his art, is similar to the political posture he adopted after the war. Emily Braun refers to Burri as a “former fascist” and maintains that he remained unaligned and politically conservative.

Burri launched his successful art career at a gallery in Rome in 1947 when he was in his early thirties. His works were included in the Guggenheim’s landmark exhibition ‘Younger European Painters: A Selection in 1953’, which is the year the Guggenheim Museum first acquired his work. Burri’s rapid ascent accelerated when the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh organized an exhibition in 1957, which it called his ‘midcareer retrospective’ (after just ten years of art-making). One can only speculate on the relation of Burri’s early success to the post-war promotion of abstract expressionism by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the United States Information Agency (USIA) as part of the plan to win over Western Europe’s unaligned and leftist intelligentsia. The US Government used, not only the Marshall Plan to assist its former enemies, but also the CIA and USIA in its anti-communist campaigns, promoting cultural exchange as a way to assert American dominance and deflect Soviet influence. Perhaps Sweeney’s patronage of Burri was in competition with René d’Harnoncourt who helped MoMA cultivate the Mexican muralists (at a time when Mexican nationalism threatened American oil interests, according to Eva Cockcroft).

Though Burri’s work is said to have had profound effects on younger American artists like Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, his popularity waned with the rise of pop art and conceptualism in the 1960s and 1970s. The Guggenheim’s 2015 retrospective of his work reveals a somewhat superficially trained artist lacking in profundity, who nonetheless opened new channels for a politically disengaged younger generation that lent its work to highly politicized purposes.

References

Gendel, Milton (1954) Burri Makes a Picture, ARTnews Vol. 53, p28 December

Jachec, Nancy (2002) ‘A Partnership of Equals’: Kennedy, the European Union and the End of Abstract Expressionism as an Atlanticist Aesthetic, Third Text Vol. 16, Issue 2, 105-118.”

Smith, Roberta (2015) Alberto Burri, a Man of Steel, and Burlap, New York Times October 8, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/09/arts/design/alberto-burri-a-man-of-steel-and-burlap.html?_r=0

Sweeney, James Johnson (1963) ‘Alberto Burri’ in Alberto Burri Oct 16 to Dec 1 1963 The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, Texas

Swenson, Kirsten (2010) (Re) Discovering Burri, Art in America Vol. 98 Issue 11, p126-131.

About the Author

Meredeth Turshen is an artist, teacher and writer who taught at Rutgers University for 34 years. She exhibits regularly in the New York metropolitan region and with the National Association of Women Artists in its various venues. She has published a dozen books in African studies, mainly about African women and African health. Her last two were Gender and the Political Economy of Conflict in Africa: The Persistence of Violence (Routledge, 2016), and Women’s Health Movements: A Global Force for Change (PalgraveMacmillan, 2020).