Forged in the Fire: Black Identity and Art

by Awendela Grantham

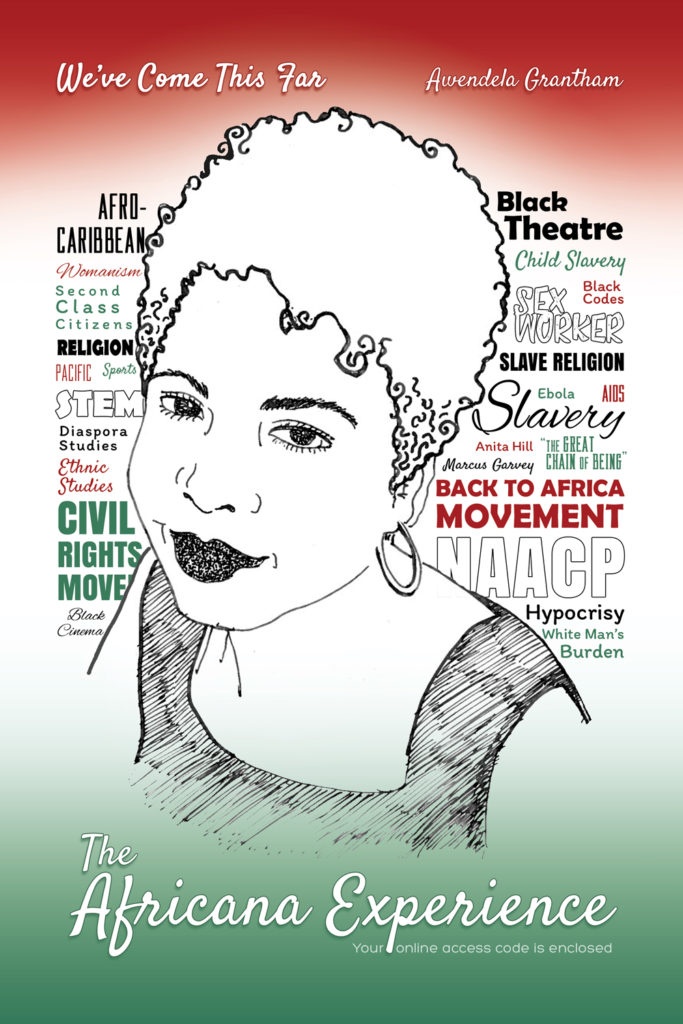

In my book, The Africana Experience: We’ve Come This Far, I write about how Europeans envisioned the continent of Africa as another world. Works like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899) depicted Africa as an uncontrolled landscape—unfamiliar, otherworldly, and evil. He represented it much like outer space. These early impressions of Africans prejudiced Europe’s (and the world’s) view of Africans, African Americans, and Black Identity.

The Black Identity in art remains elusive. Those on the outside have difficulty capturing the inner thoughts of a Black man’s soul. Black art is not just art where the faces have been “colored in” brown. The various paintings of Black people in Western Art (e.g. the “Black maid” in Édouard Manet’s Olympia, 1863) depict us as one-dimensional. These skewed and racist images obfuscate the true identity and origins of Black and Brown peoples. (The artists shunt us to the margins of society so deftly that no one even considers their portrayals racist.)

When we do not see ourselves represented in art . . . or even in history, we begin to question, “Who are we? Where did we come from? What is our true identity?”

History provides no consistent answer.

The Watts Riot of 1965 was considered the worst race riot in the country at the time. Mainstream America did not understand what Black people were complaining about. We still see this attitude today, when some commentators talk about slavery, or Jim Crow, or the prison-industrial complex. They say, “Get over it. Move on.”

There is no room for public dialogue if we cannot identify and measure the extent of what has happened. Stereotyped representations of Black and Brown peoples exist everywhere—in art, music, TV, Internet, advertising. We are polarized between those who resist (like Nat Turner, 1831) or those who “get along” with everyone (like Rodney King, 1991). Where can we find a “safe space” for constructive dialogue about race relations?

We need an open dialogue that will foster validation and change. It is time to identify the problem and take action steps that will move the country in a positive direction.

Harlem (1951) by Langston Hughes captured the spirit of our times. Beaten, redlined, and abused—we are “sagging under heavy loads.” The dreams that Martin Luther King once had remain “deferred.” The mass forces of oppression against us bind us like a pressure cooker.

Will we explode?

The psychologist, Franz Fanon supported the Algerians in their war for independence against the French (The Wretched of the Earth, 1961). He identified the theory “double consciousness,” which many people of color felt at the time.

Double consciousness is like having two identities. It is “the way people see me on the outside” vs. “who I really am on the inside.” These stereotyped representations in the media generate confusion. A young man says, “The person they see is not really me.” Convicted felon. Drug abuser. Deadbeat dad.

This pressure can cause someone to explode.

James Baldwin reported about the structural racism that we experience, and its connections to the government and capitalism in America. In The Fire Next Time (1963), he described his spiritual journey as he saw first-hand the hypocrisy of American culture toward Black people: He wrote,

“People who cannot suffer can never grow up, can never discover who they are. The man who is forced each day to snatch his manhood, his identity, out of the fire of human cruelty that rages to destroy it . . . if he survives his effort, and even if he does not survive it . . . He achieves his own authority, and that is unshakeable.”

Baldwin provoked us to probe beyond the superficial and forge new identities. The Black struggle is the struggle to be recognized and loved as a human being.

We are translated into various forms and meanings. We cannot control them. Though we may be tempted to see ourselves through other people’s eyes, we must contest and redefine these stereotyped representations of ourselves. The things people say about us, the way we look, the way others treat us—these are not who we are. Who we are is greater than the past, and our truth has yet to be discovered.

About the Author

Dr. Awendela Grantham teaches history at North Carolina A&T State University. She has published The Africana Experience: We’ve Come This Far and TROPES: Church Politics & Its Impact on the Black Female Identity.