Lessons from 75 Years Ago: Writer and Artist Ceija Stojka on the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen, the Typhus Epidemic, and Remembering Ravensbrück

by Lorely French

In difficult times like these, humans search history to learn, compare, contrast, soothe. Recounting past epidemics and pandemics is easily done—medieval Europe’s plagues, the Spanish flu, the Hong Kong flu, AIDS, SARS, Swine flu, Ebola, the list goes on. Epidemics creep up unawares, grab us by the skin, lungs, brain, and heart. Looking for sources, cures, vaccines, preventive measures, escapes, help, guidance, we marvel at human resilience and lament the speed of forgetting the number of lost lives, the pain, the sorrow.

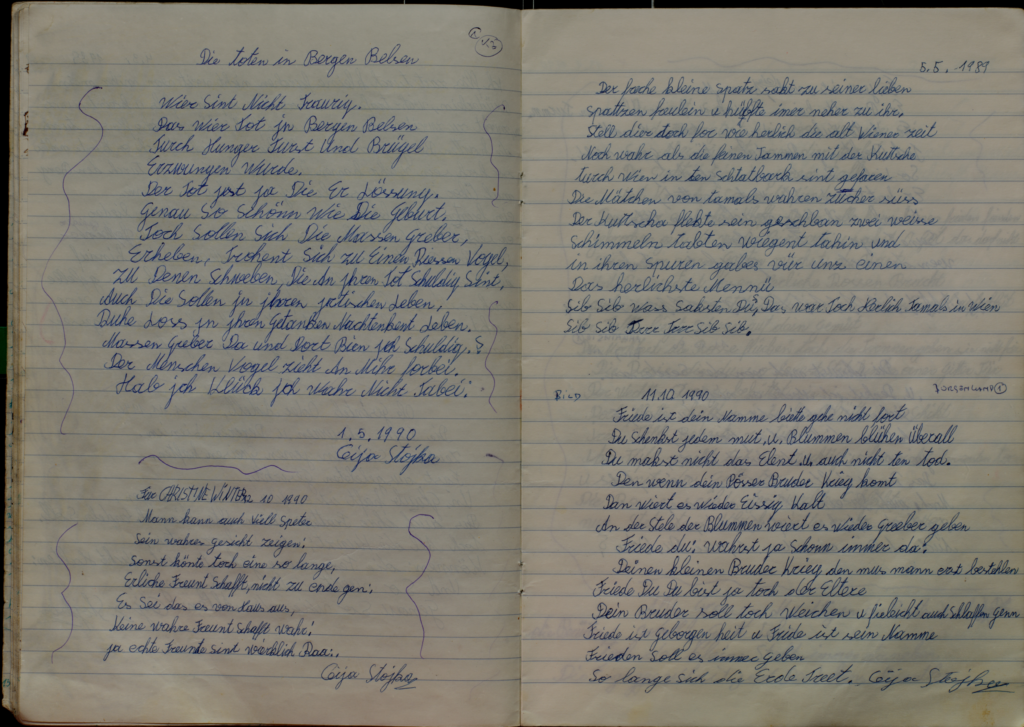

When the first official e-mail warning about the dangers of COVID-19 hit my university inbox on January 31, 2020, I was in the throes of finishing my translation from German to English of the memoirs of the Austrian Romni “Gypsy” writer, visual artist, and activist Ceija Stojka. Born in 1933, the same year that Hitler became Chancellor of Germany, she belonged to a traveling Lovara family, one of the five major Romani groups in Austria at the time. The Lovara were known for their livelihood as horse traders. On October 17, 1939, the so-called “Festsetzungserlass” [Decree to Remain Sedentary] was issued, which forced Roma to stay at their present location. Nazi persecution continued to mount, and in March, 1943, Ceija was deported with her mother and five siblings to Auschwitz. As a child, Ceija survived Auschwitz as well as the Nazi camps of Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen. After the war, she earned a living selling fabrics door-to-door and rugs at markets throughout Austria. Only in the late 1980s—after she began to fill notebooks privately with her thoughts, poems, and drawings, a practice that continued for years—did she begin to tell her story publicly through words and art.

I experienced the life-changing fortune of personally knowing Ceija (because of this connection and her charismatic personality, I only feel comfortable referring to her by her first name, or by her full name, but not by just her last name “Stojka”) during the last ten years of her life. When she died in 2013, I vowed to help make her important writings more accessible to an English-speaking readership. Now seems the right time to show not only her resilience in surviving the horror of the camps but also, through her observations of typhus deaths, to raise questions about the handling of present-day disease-borne crises.

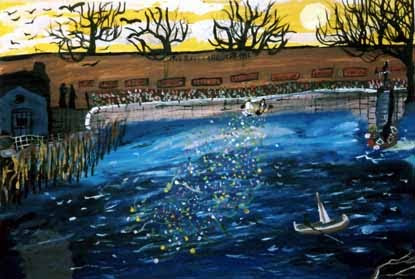

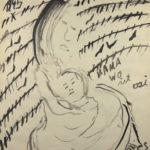

I spent a part of my sabbatical year 2018-19 researching in the archives of Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen and visiting sites in Austria where Ceija traveled with her family. I collected copious background material to annotate my translation. In April, 2019, I attended the emotionally gripping events commemorating the 74th year of liberation of Ravensbrück, the largest women’s concentration camp on German territory. Over the next 40 years after Ravensbrück’s liberation, Ceija turned to her brush to paint numerous stunning artworks depicting prisoner mothers in Ravensbürck cradling their children in their arms, and the omnipresent bestial female guards watching over them. With the same immediacy, Ceija turned to her pen, documenting her visual creations with words and texts that she scrawled in large, uneven letters on the front and back. An eerily beautiful, large painting that she gifted the Ravensbrück archives after the 50th-year commemoration of the camp’s liberation depicts her and her daughter-in-law Nuna Stojka throwing roses into the Schwedtsee, the lake on which the camp lies. This annual tradition of throwing roses into the lake and watching them slowly sink is a remembrance to the dead whose ashes the Nazis had uncaringly tossed there. On the back of the painting she writes:

“We scattered colorful flowers, Ceija and Nuna, Ravensbrück Women’s Camp. Outside of the camp is the execution place and the crematorium. The ashes of our dead were shaken into the lake. Today, in 1995, for the first time, I finally understand why it was so cold in the camp in 1944. And today people go fishing here for fish. It’s inconceivable that people living today catch fish for themselves in this lake, here where our souls rest in the ashes. ” (Memorial Museum Ravensbrück, V2207 L1, trans. Lorely French)

On November 22, 2019, I was in the Reina Sofia museum in Madrid, Spain—the same museum that houses Picasso’s massive, emotive anti-war painting Guernica—to revel at the gala events surrounding the opening of the exhibit of over one hundred artworks by Ceija, entitled “Ceija Stojka: Esto ha pasado/This has happened,” a powerful testimony to human fortitude and creativity. The exhibit received worldwide media attention. On January 27, 2020, one day before the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of Auschwitz’s liberation, Jason Farago wrote in the New York Times about the “full intensity of [Ceija’s] art,” that serves as not only “a testimony to an occluded genocide” of Roma but also to “the possibility—even the necessity—for human creativity to represent, and take ownership of, the darkest chapters in history.” I was elated to see Ceija’s artworks receiving the attention they deserved.

As the warnings about COVID-19 became increasingly stronger throughout February and then into March this year, the planned large public gatherings to commemorate 75 years since the liberation of Nazi concentration camps faded into the background and then disappeared altogether. Some were replaced by video messages, others postponed until further notice. Still intensely preoccupied with Ceija Stojka’s life and works, however, I realized that now more than ever we cannot forget this dark chapter of history. Rather, we should let the memories of the witnesses remind us of the capacity of human terror to inflict deadly diseases, to allow illness to fester when racism, greed, violence, terror rule.

As April 15, 2020 approached with no signs of the coronavirus abating, the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp by the British became increasingly more relevant. On that day in 1945, between 3:00 and 3:30 p.m., a unit of the British 63rd Anti-Tank regiment led by Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Ian Griffith Taylor and Captain Derrick Sington reached Bergen-Belsen. The liberators found around 60,000 survivors, many infected with typhus that had reached epidemic proportions. Of the total estimated 120,000 women, men, and children interned in the camp, from almost every country in Europe, approximately 52,000 perished. More than 10,000 unburied corpses lay around the huts and on the grounds. Starvation, exhaustion, and overcrowding caused the disease to spread rampantly. The mortality rate of those affected was over 60 %. To halt the spread of the disease, the liberators decided to burn the entire camp down.

Ceija witnessed the burning of the camp with her mother and her family friends: Tschiwe, another Roma mother with her two children, Burli and Ruppi, who had been Ceija’s playmates in all three camps. Ceija’s painting “Bergen-Belsen 1945” (see image above) depicting the burning of the Bergen-Belsen camp with bright orange and yellow flames engulfing the barracks was one of the moving artworks in the Reina Sofia exhibit. In her third memoir, first published in 2005, she describes her perceptions as a twelve-year-old girl:

Before we left this place my mother asked me:

“Ceija, where are Tschiwe and Burli and Ruppi?”

“Yes, Mama, they were still in their tent!”

“You’re telling me that now? They’re asleep, and the camp is burning!”

In the end the entire camp was actually burned down, the flames would have hit them directly. The camp was already cleaned out, and we were among the last who should have been taken by truck to Celle. My mother begged the English:

“Please, my sister is inside there! Please let me down!”

“But you stay here!” she told me. Naturally, I jumped down but I didn’t go that far into the camp. My mother pulled the three out, she shook them by the hair: “You have to leave, you have to fight for your lives! Look, there’s the bus bringing us to Celle and we’ll find tea and a bed there!”

Slowly they crawled out. And so we left this place. Three trucks drove one after the other, and the camp was burned down. Then the flames just sank down inside.

Of the two hundred in this section of the camp, maybe only forty survived. And after the liberation we were reduced even more. In the end, we were no more than twenty-five or thirty who eventually came out. The others died afterwards from eating too soon. (Träume ich, dass ich lebe?: Befreit aus Bergen-Belsen, 76-77, trans. Lorely French).

Before Bergen-Belsen and Ravensbrück, Ceija had experienced firsthand the ravages of typhus in Auschwitz, as her little brother Ossi had died of so-called stomach typhus, “Bauchtyphus,” while interned there. Her descriptions of the diseases in the camp distinguish between typhus [“Fleckfieber”], largely spread by fleas, and typhoid [“Bauchtyphus”], spread by fecal bacteria, both deadly diseases when left to fester in the cramped, filthy camp surroundings. Ceija’s first memoir, initially published in 1988, holds a bittersweet memory of Ossi’s final days in the infirmary:

But then our small, darling Ossi had to go to this terrible block, he had stomach typhus so bad that he couldn’t even stand up. One time I snuck into the infirmary, I crawled from one bunk to another, until I came to him. Finally, I had found him, we cried and pressed our bodies against each other. I lay down with him because no one was supposed to know I was there, that would have been bad for me. We talked very quietly with each other. I said to my little darling: “Ossi, we can go home soon, and then we’ll go to the Kongressbad swimming pool. Are you happy?” He answered me: “Look at me, I’m surely not going home anymore,” and then he added: “When you’re back home again, then you’ll think of me, yes?” Two days later my seven-year-old little brother died. [In: Wir leben im Verborgenen. Aufzeichnungen einer Romni zwischen den Welten, 24-25, trans. Lorely French).

Today, the Bergen-Belsen memorial site serves as a mass graveyard for those who had to be buried quickly in the midst of the typhus epidemic and those who could not be identified fast enough. Stone walls and gravestones dominate grassy open spaces surrounded by trees that have grown back since the burning. Ceija’s gouache painting (above) foregrounds mounds of bodies, most appearing either dead or on the verge of death. As a liberators’ tank, which Ceija has marked in her own handwriting as such with the words “1945 Befreiung Bergen-Belsen” (1945 Liberation Bergen-Belsen) rolls above the swirling masses, tears stream down the hollow face of one body staring wide-eyed at the viewer while the mouth of a helmeted head sporting a Hitler- like mustache and swastika on his arm appears to be in the act of devouring the corpse.

In her memoir about Bergen-Belsen, Ceija reflects on visiting the camp’s memorial site. Upon seeing mounds of mass graves and sensing the swirling souls the corpses lying there, she wisely defines the role that those who outlive such suffering, torture, and epidemics must play in mourning and living on for the dead: “When I go to Bergen-Belsen it’s always like a festival. The dead whiz around. They come out, they move, I feel them, they sing, and the sky is full of birds. Only their bodies lie there. They’re out of their bodies, because their lives were taken with violence. And we are their carriers, we carry them with our lives” (Träume ich, dass ich lebe?: Befreit aus Bergen-Belsen 80). Indeed, her writings and artwork celebrate these souls and remind us to transmit their messages forward.

The Reina Sofia exhibit was slated to continue until March 23, 2020. Little did I or other visitors to the exhibit know in November that less than four months later, the Reina Sofia would close due to Covid-19. A near-total national lockdown of Madrid occurred on March 14, banning people from leaving their homes except to go to essential work, buy food and medicine, or care for an ill relative. The ravages of the coronavirus pandemic hit Spain especially hard; by the end of March, the number of patients had surpassed the national capacity of some 4,400 beds, and the deaths had soared to over 7,000, with over 800 people dying every 24 hours (Devereux and Colten). Only on May 2 did authorities allow inhabitants of Madrid to go outside, albeit still under restrictive conditions.

What messages can our present pandemic carry forward? According to the World Health Organization, the number of confirmed cases globally at the time I am writing this essay has reached over 4,801,200 and the number of confirmed deaths over 318,930 (World Health Organization, “Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation”). With these numbers still increasing daily, one hopes that measures such as social distancing, providing accessible testing, and researching for a cure and vaccine will prevent taking such extreme actions as the liberators of Bergen-Belsen had to assume to stem the epidemic tides. The human creativity that Jason Farago observed in Ceija’s artwork as necessary “to represent, and to take ownership of, the darkest chapters of history” is indeed taking place: factories are turning their machines to mask making; 3D printers are making face shields; neighbors are taking grocery shopping trips for the elderly; people are finding time to meditate and talk more on the phone; museums and artists are displaying artworks virtually; musicians are performing concerts together over the internet in the space of their homes; school teachers and university professors have quickly moved their classes online.

Of course, in drawing on the Bergen-Belsen epidemic to learn about possible helpful lessons for our present pandemic, I in no way want to generalize or trivialize the vast terror that the Nazis inflicted on those persecuted, terror that goes beyond the scope of epidemics and even pandemics. Today’s times, however, are indeed uncertain, and for many, even dark. Let us thus turn to the art and writings of victims and survivors of other dark pasts, such as Ceija Stojka, who portray previous horrors and epidemics. In doing so, let us find hope for survival and discover creative means to confront trauma and to tell our stories. As Ceija’s little brother put it: “…you’ll think of me. Yes?”

Image Gallery

Acknowledgements

This essay is made possible with sabbatical funding from Pacific University and a grant from the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst/German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). I am grateful to Hojda Stojka, Simona Anozie, and Pablo Stojka for permission to reprint Ceija Stojka’s artwork; Nuna Stojka, Michaela Grobbel, and Karin Berger for their expertise; Sabine Arend, Head of the Repository Department at the Ravensbrück Memorial, for procuring the image and rights to the artwork in Ravensbrück as noted; Matthias Reichelt for photographs of the images as noted; Carina Kurta for providing scans of the notebooks; archivists and scholars at the Ravensbrück Memorial, including Cordula Hundertmark, Monika Schnell, Matthias Roth, and Dr. Insa Eschebach; and archivists and scholars at the Bergen-Belsen Memorial, including Dr. Thomas Rahe, Klaus Tätzler, Dr. Diana Gring, Bernd Horstmann, Corinna Rathjen, and Katja Seybold. Special thanks go to Dr. Pauline Beard, for invaluable editorial comments on an earlier version of the essay.

About the Author

Lorely French is Distinguished University Professor of German at Pacific University in Oregon. She is author of German Women Letter Writers 1759-1850 and Roma Voices in the German-Speaking World. She is a contributor to the digital RomArchive (https://www.romarchive.eu/en/) and sits on the board of the Ceija Stojka International Fund (https://www.ceijastojka.org/).

Works Cited

Ceija Stojka: Esto ha pasado. Exhibit Catalogue. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, en colaboración con La maison rouge -Fondation Antonie de Galbert (Paris), 22 Nov., 2019 to 23 March, 2020.

Ceija Stojka (1933-2013): “Sogar der Tod hat Angst vor Auschwitz” /”Even Death is Terrified of Auschwitz”/”Vi O Merimo Daral Katar O Auschwitz.” Ed. Lith Bahlmann and Matthias Reichelt. Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst, 2014.

Devereux, Charlie and Jerrold Colten. “Hospitals Swamped as Italy-Spain Virus Deaths Surpass 17,000.” Bloomberg. 29 March 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-29/spain-reports-record-number-of-coronavirus-deaths-in-24-hours. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Farago, Jason. “The Survivor of Auschwitz Who Painted a Forgotten Genocide.” The New York Times, published 27 January 2020, updated 28 January 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/27/arts/design/ceija-stojka-auschwitz-paintings.html. Accessed 20 May 2020.

“The Liberation of Bergen-Belsen.” Imperial War Museum. 23 January 2018. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-liberation-of-bergen-belsen. Accessed 20 May 2020.

Sington, Derrick. Belsen Uncovered. London: Duckworth, 1946.

Stojka, Ceija. Träume ich, dass ich lebe?: Befreit aus Bergen-Belsen, ed. by Karin Berger. Vienna: Picus, 2005.

—. Wir leben im Verborgenen. Aufzeichnungen einer Romni zwischen den Welten. Edited with an essay by Karin Berger. Vienna: Picus Verlag, 2013.

World Health Organization. “Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation.” https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019. Accessed 20 May 2020.