Teaching World Cinema in Lockdown

By Jennifer Gauthier

If not for COVID-19, I’d be exploring the sands of Rarotonga as you are reading this article. I planned a house swap with a colleague in New Zealand, and then a side trip to an island that has inspired me since I watched Kanaka Maoli filmmaker, Erin Lau’s digital short, Little Girl’s War Cry (2013). Lau and two classmates from The University of Manoa’s Academy of Creative Media shot the film on Rarotonga as part of The FilmRaro Initiative. With support from the Sundance Film Festival and an IndieGogo campaign, Lau crafted a powerful tale of a young Maori girl who finds the strength to stand up to her mother’s abuser. The film is available on Vimeo and I urge everyone to watch it.

My research in media studies focuses on Indigenous cinemas around the world, and I am privileged to have been able to travel. At my small, liberal arts college in Southwestern Virginia, many students are not. Due to global politics and economic constraints, more of our students are coming from the contiguous states. Many are local, from one of the counties that surround our small city and have not had the means or opportunities to travel. As a result, they have not been exposed to people who are different from them – people of different races, ethnicities, or religions.

I am firmly committed to educating my students to learn about the world, to challenge power relations, and to agitate for positive change. I want to empower them to confront injustice and inequality. Often, the first hurdle is to get them to think about their connections to other people who do not look, act, or think like them.

This is where cinema comes in. People love movies. Although theaters are empty, streaming services are booming – witness the recent rise in subscriptions to Netflix and the early success of Disney+ (Shapiro). Many people’s lives are now fully lived in front of the computer – during work hours and in their free time. Although many people consume movies as a leisure activity, foreign films have a small audience and thus, a shrinking distribution (Kaufman).

This is where cinema comes in. People love movies. Although theaters are empty, streaming services are booming – witness the recent rise in subscriptions to Netflix and the early success of Disney+ (Shapiro). Many people’s lives are now fully lived in front of the computer – during work hours and in their free time. Although many people consume movies as a leisure activity, foreign films have a small audience and thus, a shrinking distribution (Kaufman).

Here I want to argue that cinema can play an important role in encouraging empathy and understanding across cultures and identities. While this insight is not a new discovery for me, its importance was highlighted while I taught World Cinema during the pandemic lockdown. Moving to remote classes halfway through the semester was both a curse and a blessing. I had purchased films and made plans for screening them on campus with my students. Our weekly screenings were a special bonding time: I would bring snacks and we would settle into our seats in the theater-style classroom to enjoy the film as a group. These communal viewings are an important part of the class, as we get to experience each other’s reactions to the films – hear exclamations, or laughter, or a heavy silence at the end. For me, the moments immediately following a screening are a powerful indicator of how students feel about a film: their comments, or lack thereof as they gather up their belongings and leave the room, or their questions to me, speak volumes.

When the pandemic struck, my family and I moved to a location outside of town. I wouldn’t say I am a germaphobe, but I feared the post-Spring Break influx of students returning to the largest Evangelical Christian university in the world, which sits a mere eight miles from our campus. Moving online allowed me the luxury of teaching from wherever I chose to shelter, but it meant that in-person film screenings would end.

Not being together to watch the films for class was sad enough, but I also faced the challenge of figuring out how my students could view the films I assigned. The last five weeks of the semester focused on cinemas of the global South, or other non-mainstream cinemas. Films from this region are particularly difficult to find in the U.S, due to what Herbert Schiller describes as “structural exclusion” (159). The American mediascape is a capitalist oligopoly with a shrinking number of conglomerates who control the production, distribution, and exhibition of the media. The top four media companies control 90% of the culture we consume on a daily basis, and their primary goal is to make a profit (Molla and Kafka). As a result, alternative voices and viewpoints are often ignored because they are not seen as popular (read: profitable).

The tools at our disposal for an online World Cinema class have expanded – this is undeniable. We have subscription services like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Kanopy, not to mention YouTube, Vudu, and iTunes. Some independent and global films can be found on these services, but they are likely to be those that have received widespread recognition. Moreover, the services often charge extra for viewing “foreign” films – fees over and above the monthly subscription cost. I am unwilling to ask my students to spend more money on a class for which they have already paid tuition. The financial burden of higher education has skyrocketed. We are pricing people out of the experience and reifying structural inequality in the process.

My goal was to find films that introduced students to cultures other than their own, that were available free with their existing streaming subscriptions. To achieve this goal, I had to completely change my syllabus for the final weeks of the course, which forced me to expand my thinking about which films to include.

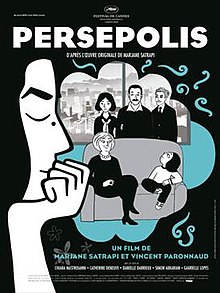

Despite the inconveniences, we shared some remarkable experiences. All of my students were able to watch a Third Cinema film, The Battle of Algiers (Gillo Pontecorvo, 1966); a Bollywood film, Dilwale Dulhenia La Jayenge (Aditya Chopra, 1995); short documentaries and animation made by Inuit filmmakers from Canada; and Taika Waititi’s Boy (2010). For our week on Iranian cinema, due to a change in the streaming provider’s catalogue, some students watched Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi, 2007) and others watched Ava (Sadaf Foroughi, 2017). Students were able to take advantage of services they already used (Netflix or Amazon Prime) and a college subscription allowed them to watch films on Kanopy. Canada’s National Film Board has digitized a large portion of their catalogue and many Indigenous films are available for viewing online

Finding the films was not the only challenge we faced. Half of my students live in rural areas where the Internet access is poor and many were also juggling the technology needs of their parents and siblings – they had to watch the films in short pieces.

Overall I was pleased with how the semester turned out. Most of our discussions (via Google Meet every Tuesday for an hour) were well-attended and lively. Students were engaged in all of the films for a variety of reasons. They were horrified by the violence depicted in The Battle of Algiers and also entranced by its documentary-like quality. The pairing of Persepolis and Ava yielded a rich discussion about the struggles of young women chafing against their strict Iranian culture and parental expectations. Students loved DDLJ because of its resemblance to an American romantic comedy. Similarly, they related to the Indigenous films we watched by focusing on the universal themes of family, identity, grief, and joy. I felt it necessary to point out what made these films unique – the specificity of religion and politics in Iran, the Indian-British cultural hybridity of DDLJ, and the state-sponsored racism toward Indigenous people that provides context for the Inuit films and Waititi’s Boy.

Overall I was pleased with how the semester turned out. Most of our discussions (via Google Meet every Tuesday for an hour) were well-attended and lively. Students were engaged in all of the films for a variety of reasons. They were horrified by the violence depicted in The Battle of Algiers and also entranced by its documentary-like quality. The pairing of Persepolis and Ava yielded a rich discussion about the struggles of young women chafing against their strict Iranian culture and parental expectations. Students loved DDLJ because of its resemblance to an American romantic comedy. Similarly, they related to the Indigenous films we watched by focusing on the universal themes of family, identity, grief, and joy. I felt it necessary to point out what made these films unique – the specificity of religion and politics in Iran, the Indian-British cultural hybridity of DDLJ, and the state-sponsored racism toward Indigenous people that provides context for the Inuit films and Waititi’s Boy.

What students took away from the semester, particularly the latter half with its exclusive focus on de-colonial cinema, were the simultaneous differences and similarities between human cultures all over the world. They empathized with the struggles of young lovers to be together despite overbearing parents, the challenges of forging an individual identity in the face of strict social norms, the grief felt over losing your home, and the joy of freedom. I hope they also learned to seek out alternative voices and viewpoints, no matter how difficult it may be to find them. Our digital world may be expanded but it is still exclusive. In my search to find films online I modeled for them that this effort can unearth eye-opening experiences.

My World Cinema course reminded me that film is a powerful tool for creating empathy and understanding. But even if you don’t use film in your classes, all of us need to do a better job of making sure that marginalized voices are included, valued and heard. It’s the only way anything will change.

References

Kaufman, Anthony, “The Lonely Subtitle: Here’s Why U.S. Audiences Are Abandoning

Foreign-Language Films.” IndieWire.com. 6 May 2014. https://www.indiewire.com/2014/05/the-lonely-subtitle-heres-why-u-s-audiences-are-abandoning-foreign-language-films-27051/

“Little Girl’s War Cry – A Cook Islands Short Film.” IndieGogo.

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/little-girl-s-war-cry-a-cook-islands-short-film#/

Molla, Rani and Peter Kafka, “Here’s Who Owns Everything in Big Media Today,” Vox.com. 5

December 2019. https://www.vox.com/2018/1/23/16905844/media-landscape-verizon-amazon-comcast-disney-fox-relationships-chart

Schiller, Herbert. Living in the Number One Country: Reflections from a Critic of American

Empire. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2000.

Shapiro, Ariel. “The World’s Largest Media Companies 2020: Comcast And Disney Hold A

Precarious Lead.” Forbes.com. 13 May 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/arielshapiro/2020/05/13/the-worlds-largest-media-companies-2020-comcast-and-disney-hold-a-precarious-lead/#359025d7469c

About the Author

Jennifer Gauthier is a professor of Media and Culture at Randolph College in Lynchburg, Virginia. She teaches courses in media studies, gender studies and rhetoric and coordinates the minor in Film Studies. She is the recipient of two Fulbright Awards to Canada and her research on Indigenous media and cultural policy, gender, and activism has appeared in scholarly journals and edited collections. Her current book project examines films made by Indigenous women in Canada.