by Dr. Frances Pinter

About five years ago I ran across a book by UCLA Professor Christine Borgman – Big Data, Little Data, No Data where she draws from a report authored by Paul Edwards, herself and others. They define Knowledge Infrastructures (KI) as:

…robust networks of people, artifacts, and institutions that generate, share, and maintain specific knowledge about the human and natural worlds. In this framing, the distinguishing features of a KI are ubiquity, reliability, and durability: when a KI breaks down, it results in social and organizational chaos. A KI is not one system, it is instead a multi-layered, adaptive effort in which numerous systems, each with unique origins and goals, are made to interoperate by means of standards, socket layers, social practices, norms, and individual behaviours that smooth out the connections among them (Edwards et al).

Borgman argues that each academic discipline has its own knowledge infrastructure. These include the buildings, the places of activity, the people, the communications networks and, of course, how research is published and disseminated. It’s a complex ecology.

Knowledge infrastructures reinforce and redistribute authority, influence and power – and this has profound impacts both within and outside of these KIs.

As a result of the global pandemic we are about to see some huge changes. Contractions of higher education institutions will make the headlines. There will be redundancies amongst faculty and with that, reductions in library budgets. How much, we do not yet know, but it won’t be evenly spread out. Parts of knowledge infrastructures will contract faster than others: a few may expand, but there will definitely be a scrabble for resources and a chaotic adjustment period. It is likely that the Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) will suffer more than STEM – at a time when we need more than ever to learn about ourselves so that we can better cope with the global challenges that threaten the very existence of humankind.

I believe that with some much overdue changes to the way the we publish monographs, we can use this crisis to mark a commitment to reducing costs while improving dissemination of these specialist monographs that provide the foundational basis for development in the HSS subjects.

The key to this is Open Access (OA). For that to succeed, we need to work on four aspects of monograph publishing. The first aspect is the funding – which will come if we can demonstrate that the demand is there, that monographs are good value for the money, and that costs can be reduced significantly. The second aspect is that we need business models through which funding can be channelled efficiently and cost effectively. The third aspect is to produce the right kind of metadata that stays constant throughout the life cycle of a book. Finally, we need to find ways in which OA can sit visibly alongside other formats, such as print, that should continue to be available where there is a demand.

The first is easy. When over 80 publishers allowed their books to be freely accessed from mid-March to the end of July 2020, usage rates skyrocketed. Here are just a couple of examples from the MUSE platform:

- Johns Hopkins University Press made 1553 titles across the range of monographs, professional, reference, and academic trade books open on the MUSE platform – usage each month grew to 3000% before reverting to closed access.

- CEU Press, with its narrower range of predominantly monographs, experienced a massive 315,000 visits on the MUSE platform alone for its 300 titles – accessed in 129 countries.

These sorts of figures need to be championed around institutions so they can see the benefit of OA. Mandates are also an important factor. While Plan S comes into force for publicly funded research resulting in journal articles throughout much of Europe in 2021, it is expected that monographs and edited collections will fall under the same mandate by 2024. In the US, the Office of Science & Technology Policy is looking at OA as a way to enhance public access to federally funded research. While OA mandates remain controversial, they are not likely to disappear, especially with evidence of the benefits having become clearer over the past few months.

At the same time, publishers are looking for ways to reduce the cost of producing monographs without sacrificing quality. An example here is the Sustainable History Monograph Project .

Next, there are several business models that work for OA monographs. Just as there is great variety in the types of monographs published, we have a number of sources for funding and ways of channelling those funds into OA programs. Some examples are listed here:

- Research Funding Bodies – see Plan S

- Institutions – central funds to support OA – Lever Press

- University Departments – many small hidden pockets of money

- Crowdfunding – Knowledge Unlatched , Unglue.it

- Foundations – Wellcome Trust

- Membership – Open Book Publishers

- Collective models – Luminos

One area where there is much work to do is improving metadata. We need to agree on standards and apply them consistently. Metadata is often altered on its way through the system to serve the particular needs of anyone along the road to discovery. This can clog the system and result in poor search results. If everyone agreed on a core set of minimal metadata, then success in discovery and finding monographs would show a huge increase. This would also help improve usage data — another essential part of feedback on scholarly publications.

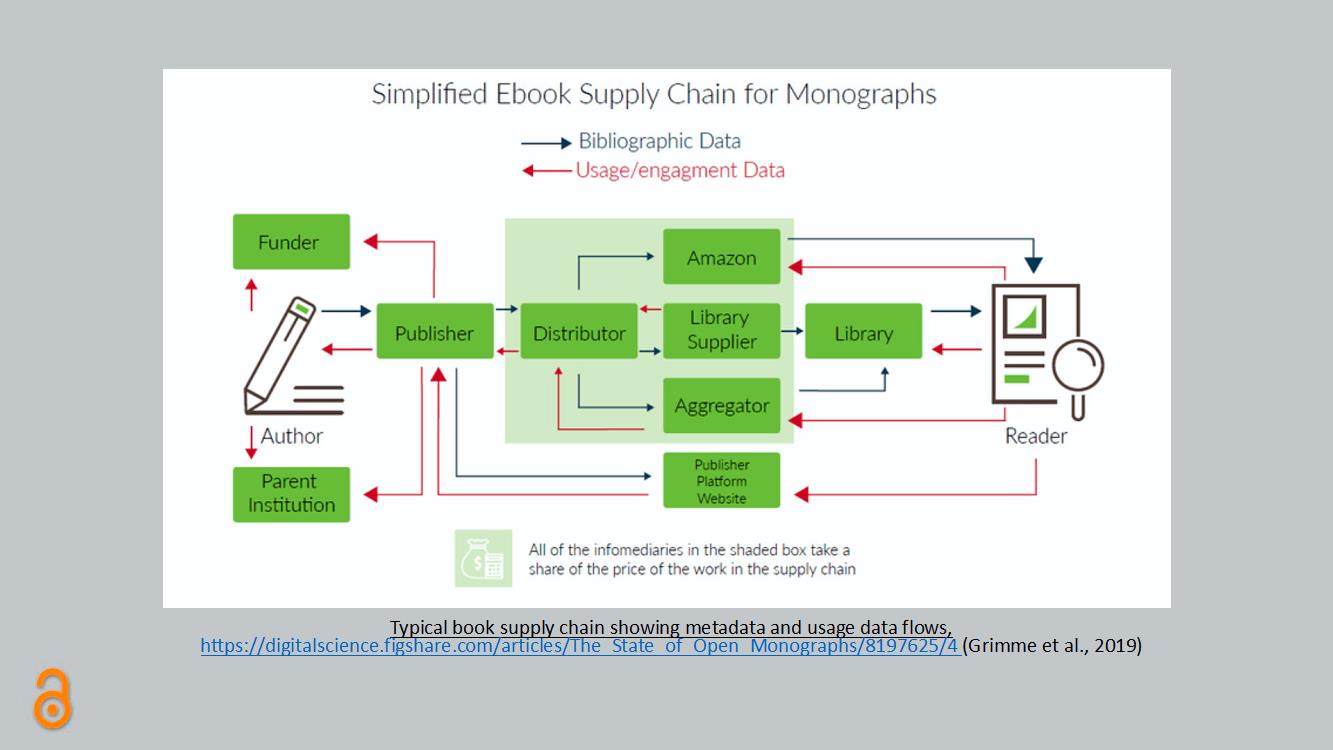

Everyone along the supply chain needs to better understand what role the intermediaries can and perhaps should play in the dissemination of OA content. But to get to that point, we need a better understanding of what their charges are buying currently. The light green box in the diagram below indicates where we lack sufficient information about the costs being applied, and therefore, the price of the book at its final destination.

Too often, OA content resides behind a bush and its full value cannot be achieved. Because the availability of OA books is often unknown, already stretched library budgets are sometimes spent unnecessarily. There is little incentive to intermediaries who make a living selling content, yet there could be a role for them in effectively distributing metadata in this new OA world. We also need ways of selling books to those who want and can afford the printed text. This should be encouraged as print sales help to provide support for sustainable OA.

The period ahead of us will be one of great changes to the academic knowledge infrastructures. It could also be a period when having grasped the value of OA for HSS, all stakeholders contribute to making the changes necessary to provide cost effective and easily discoverable Open Access monographs.

The pie may well be smaller, but we have a choice. Either all sectors fight one another for larger parts of the smaller pie, or we get smarter about how we do things. And for this, Open Access is the way to go.

Dr. Frances Pinter is Executive Chair for the Central European University Press. Learn more about Dr. Pinter’s work and projects here: http://www.pinter.org.uk/.