by Linda English, PhD

In December 2016, the co-program directors of the Gender and Women’s Studies Program (GWSP) at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley received the good news that their application for a National Endowment to Humanities Initiative Grant to revitalize the GWSP at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley was approved. The following is an overview of the implementation of the NEH grant, a 20-month project entitled “Revitalizing UTRGV’s Gender and Women’s Studies Program” beginning in the spring of 2017 through its conclusion in August 2018. It highlights the insights, experience, and recommendations of external consultants who participated in the grant; specialists who oversee successful gender, sexuality, and women’s studies programs across the country . The distinguished specialists who visited campus over the course of the grant generated both interest in gender-related topics among our students as well as excitement for the field of study among our affiliated faculty.

In the fall of 2015, a new university opened its doors to students in deep-south Texas: The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. UTRGV brought together the resources and assets of two legacy institutions: the University of Texas, Brownsville (UTB) and the University of Texas, Pan American (UTPA). At the time of the merger, the Gender and Women’s Studies Program faced the challenges associated with the creation of a new university: faculty reorientation and adjustment as well as the reworking of the program’s infrastructure. The project was undertaken by a group of ten faculty members from UTRGV’s College of Liberal Arts dedicated to developing a flourishing program focused on gender studies. Affiliated with GWSP, they researched and taught in the fields of history and philosophy as well as literature, languages, and cultural studies. The plan was to incorporate best practices from successful programs at other universities as well expand UTRGV’s course offerings into areas of emerging scholarship. We wanted to analyze how we could improve our curriculum to (re)build a consistent, high-quality program. Strengthening the GWSP in this way provided new opportunities for faculty to expand their scholarly horizons and to study together to become well-versed and effective teachers. Ultimately, we believed that we could not achieve such goals without external input and support.

To do so, the project was divided into two major phases. The first phase focused on assessing and improving the overall organization and structure of the GWSP. The second phase was dedicated to creating new opportunities for UTRGV’s faculty to deepen their knowledge in the fields of women’s, gender, and sexuality studies and thus become more-informed teachers. The first phase was comprised of four workshops dedicated to assessing the GWSP—its shortcomings and its potential. During the first internal workshop in February 2017, the project directors and the affiliated faculty met to:

- discuss faculty’s experience in teaching and researching in the field of gender, women’s and sexuality studies;

- assess the current status of the GWSP (enrollment at this point was six students, enrollment history, degree plans and courses etc.);

- and exchange ideas and opinions about future directions of the GWSP (its mission, its focus, and its goal).

The subsequent months of March, April, and May 2017 featured workshops with invited, external consultants who had in-depth knowledge of establishing, running, and enhancing gender-focused programs. Each workshop consisted of a 30-45 minute-long presentation (plus Q&A session) by the invited consultant about their work and program; followed by a 2 hour-long work and discussion session that focused on how UTRGV’s GWSP could be revised and enhanced.

After the internal workshop with affiliated faculty, the external consultants began their campus visits. The first external consultant was Dr. Jennifer Lynn from Montana State University, Billings who led a workshop titled “From Women to Gender? Pitfalls and Opportunities.” Dr. Lynn detailed the evolution of the Women and Gender Studies program at Montana State. She also stressed the importance of a dedicated space on campus for program visibility and her program’s successful efforts at community outreach (in particular, a brown bag session opened to both students and community members). The second external consultant to visit UTRGV was Dr. Guillermo De Los Reyes from the University of Houston whose workshop was titled “Integrating Sexualities into a Gender and Women’s Studies Program.” Dr. De Los Reyes provided an overview of the Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program at the University of Houston. He traced the development of the program from a minor to a major and the success of the in their introductory course in the core (over twelve classes per semester, four sections of LBGTQ core class). He also discussed community outreach and fundraising, particularly the Friends of the Women’s Studies Program which raises funds for research and travel grants. The last external consultant for first phase of the grant was Dr. Lorraine Bayard de Volo from the University of Colorado, Boulder. Dr. Bayard de Volo discussed some of the early obstacles of the program and its evolution from a minor to a major. She also discussed certificate options for UC-Boulder students, including an LBGTQ Certificate and Global Gender & Sexuality Certificate. Her discussion included the challenges of offering a global gender perspective.

After the spring campus visits, the program directors led two summer retreats for participating affiliated faculty. Both retreats focused on examining and integrating the suggestions provided by the three external consultants. The two retreats were titled: “Evaluating External Input and Defining Future Steps” and “Implementing External Input and Internal Evaluation.” Participants from the spring workshops were invited to contribute. At the first retreat, we focused on our outward “face” to students. This entailed articulating our mission, developing rationale as to why to study gender (through a minor or certificate), and creating a glossary of terms for our website. The second retreat involved planning for the fall semester, including developing syllabus for an introductory course on Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies.

The second phase of the initiative was dedicated to creating new learning opportunities for the faculty associated with the GWSP by inviting six gender content specialists to campus. The first of our six invited content specialists arrived in September 2017 to conduct a pedagogical workshop for our affiliated faculty in the morning and provide a public lecture for the UTRGV community in the evening. The audience was twofold: the GWSP affiliated faculty and UTRGV faculty, students, and the public at large. The public lecture served to generate general interest in gender topics and our program, more specifically. Our first invited content specialist was Dr. Nicholas Syrett from the University of Kansas. We had planned on three specialists for the fall and three for the spring, but due to a scheduling conflict, moved the lecture schedule to two in the fall and four in the spring. Our second content specialist, Dr. Michelle King, from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, came to campus in early December and offered a global-focused workshop and public lecture titled, “The Julia Child of Chinese Cooking, or the Fu Pei-mei of French Food? Comparative Contexts of Female Culinary Celebrity.”

Beginning in January 2018, the GWSP invited four content specialists to campus to, once again, lead a morning workshop for affiliated faculty (focused on strategies for incorporating gender into our teaching) and provide a public lecture that evening to the UTRGV community. The four specialists were Dr. Nancy Hirschmann (University of Pennsylvania), Dr. Crystal Feimster (Yale University), Dr. Robert Irwin (University of California, Davis), and Dr. Emma Pérez (University of Arizona). With four campus visits during the spring semester, our affiliated faculty were especially busy, but the experience proved extremely rewarding; the content specialists provided the faculty with valuable insights on “teaching gender” and the public lectures galvanized interest in our program and gender topics, more broadly. For example, Dr. Feimster focused much of the workshop on demonstrating some of the innovative class projects that she assigns to her students that encourage both creativity and analytical thought. These assignments included having her students create “zines,” initially the assignment focused on Pauli Murray; as well, she has her students develop a children’s book (she brought examples from her classes). Affiliated faculty created their own “zines” in the workshop. Dr. Pérez introduced an exercise to the workshop participants where they wrote 1st person accounts on: “I used to be ______ and now I am _________.” Dr. Perez’s public lecture was the largest of all, with over two hundred students and faculty in attendance. In the summer 2018, we organized a three-day retreat for affiliated faculty that enabled faculty to perform teaching demonstrations, incorporating some of the strategies they gleaned from the 2017-2018 pedagogical workshops.

The grant concluded after the 2018 summer retreats. The monies provided by the NEH allowed the GWSP to increase its exposure to the UTRGV community; consequently, we have seen the program grow in popularity. We developed an introductory course for the GWSP, “Introduction to Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies,” offered at least once a year, which generates student interest in the GWSP minor and certificates. Indicative of faculty interest in gender-related fields, the affiliated faculty has grown from the original ten to a robust 35 affiliates.

About the Author

Dr. Linda English is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. She teaches courses on Texas History, the American West, Modern American Women’s History, and Gender in the American West.

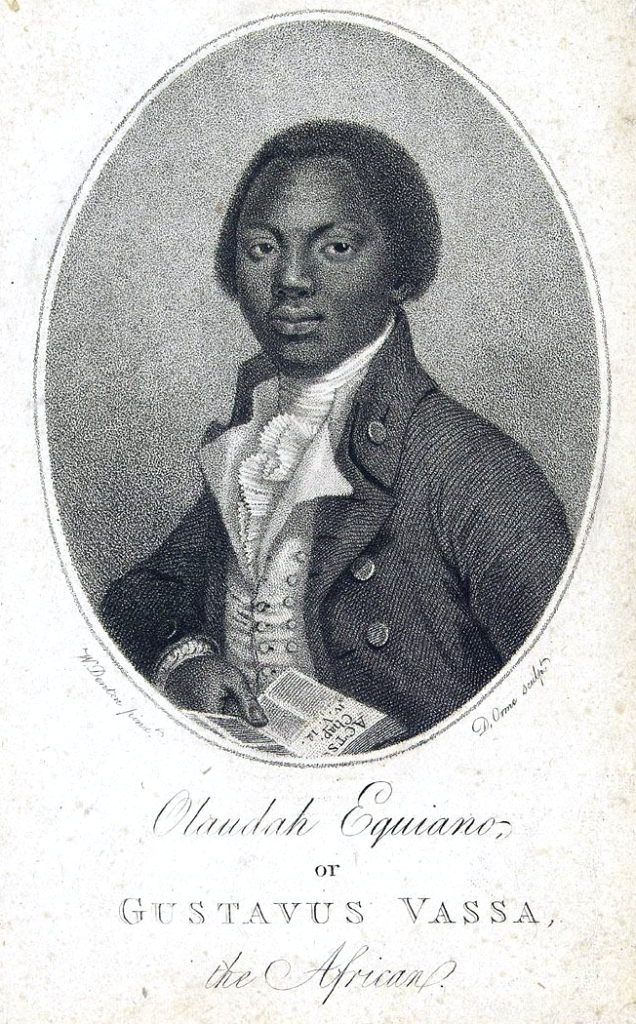

“The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or Gustavus Vasa, the African, written by Himself.” These tickets should be easy to sell, she thought. A story of life in Africa, kidnapping, enslavement, the Middle Passage. It’s eighteenth century HipHop. A man claims himself and defies the odds. It’s edgy; it’s truth revealed. Certainly the students who chose to go to a Historically Black College would be engaged, maybe even excited. Two young women arrive on time, one perpetually on her phone and the other hiding behind her computer. Thirty minutes into class, two young men come in, one completely empty handed, the other with a pencil and spiral notebook through which he shuffles trying to find a blank page. With ten minutes of class remaining, she gets their attention with the question, “How do we dehumanize people now?” She leads them by the nose, connecting the dots: slaves were dehumanized to legitimate atrocities against humanity; after 911, Muslims were dehumanized to increase fear and legitimate a war; Trump used tear gas on peaceful BLM protests for a photo-op at his convenience and a platform of “law and order.” How much has changed, she asks as she steps hopefully out onto her right pointe shoe, leg poised to elevate, but never coming off the floor.

“The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or Gustavus Vasa, the African, written by Himself.” These tickets should be easy to sell, she thought. A story of life in Africa, kidnapping, enslavement, the Middle Passage. It’s eighteenth century HipHop. A man claims himself and defies the odds. It’s edgy; it’s truth revealed. Certainly the students who chose to go to a Historically Black College would be engaged, maybe even excited. Two young women arrive on time, one perpetually on her phone and the other hiding behind her computer. Thirty minutes into class, two young men come in, one completely empty handed, the other with a pencil and spiral notebook through which he shuffles trying to find a blank page. With ten minutes of class remaining, she gets their attention with the question, “How do we dehumanize people now?” She leads them by the nose, connecting the dots: slaves were dehumanized to legitimate atrocities against humanity; after 911, Muslims were dehumanized to increase fear and legitimate a war; Trump used tear gas on peaceful BLM protests for a photo-op at his convenience and a platform of “law and order.” How much has changed, she asks as she steps hopefully out onto her right pointe shoe, leg poised to elevate, but never coming off the floor. Elizabeth Kuipers’s love of teaching began in

Elizabeth Kuipers’s love of teaching began in