by Prof. Belenna Mesa Lauto

Author’s Note

This article discusses the work of Lennart Nilsson and his work as it relates to one of the most controversial topics of the 21st century: the sanctity of life in the womb. The evidence published by biologists, chemists and of course, photography reveals the critical nature of facts vs. emotions and how we, as humans respond, which also gives way to psychological studies in regard to human emotion and response. The information presented is not intended to provoke a particular narrative, but rather as a sincere examination of facts as the humanities, in particular: art, history, biological sciences and psychology all provide evidence of facts through observation and study.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Lennart Nilsson was working as a photojournalist in his early twenties. His first published essay at age 22, Midwife in Lapland, (or Midwife in the Mountains), documented the work of Siri Sundström, a midwife working in the mountains in the Swedish wilderness, Arjeplog. This very early work brought light to this amazing woman, who had helped over 2,500 women give birth safely.

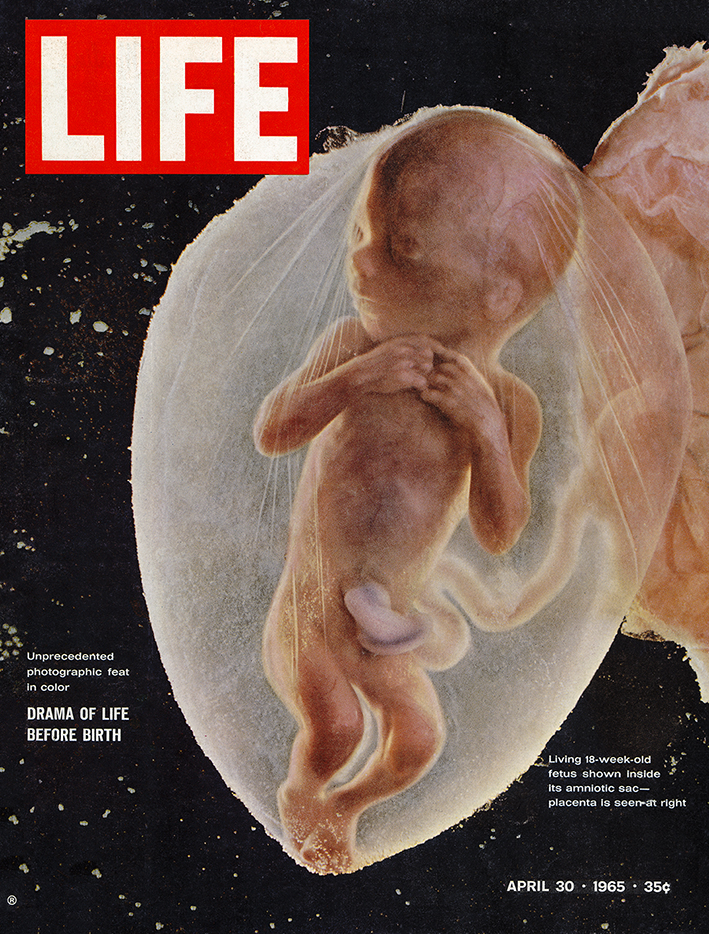

Nilsson’s early interest in life and science, as well as his poetic sensitivity to the communicative power of images is clearly evident in this photographic essay. His ability to visually and systematically communicate facts gave him an iconic place in photography’s history and in 1945, his passion for science and technology moved him to pitch an idea to LIFE Magazine for a story on life in the womb. The essay, Drama of Life Before Birth, took seven years to complete as he collaborated with doctors and scientists throughout Stockholm. I was only five when the essay in LIFE was published. I discovered it while perusing books about the “photo essay” while in the library of my high school. I was fifteen. As it turned out, my weekly trips to the library pivoted my “career goals” from writing to photography. Nilsson and photographic icon, E. Eugene Smith were responsible. What I couldn’t say with words, photography would articulate…science, art and communication at play, often providing provoking evidence of what we choose to ignore.

In November 1991, at the Foto Massan, Swedish Association Photographic Convention in Gothenburg, Sweden, I met Lennart Nilsson. We spoke for just a few minutes, but the few words that we exchanged revealed an undeniable truth that pierced my heart and mind. By now I was well established in my photographic career and also in line for tenure at St. John’s University. Remaining an avid fan of LIFE Magazine, though no longer a publication, Nilsson’s images flooded my mind once again. In April 1965, LIFE published his “story” and featured his photograph of a fetus at 18 weeks on the cover. It was the fastest selling issue in LIFE Magazine’s entire history and the embodiment of Nilsson’s commitment to “capture the beginnings of human existence”, which would occupy fifty years of his photographic work.

Fetus 18 Weeks is considered one of the 20th century’s great photographs, but the extensive work Nilsson accomplished is even more impressive. I gathered the courage to tell him how his images touched me. He smiled, but his smile held great wisdom and peace. Then I asked what is probably one of the most ridiculous questions I have ever asked: “What is your position on abortion after completing this work?” He smiled again, and responded with a heavy, distinguished Swedish accent, “Young lady, I thought you just said you were familiar with my work.”

Nilsson’s response immediately provoked me to do more research and re-examine his work from the perspective of scientific evidence, which is what he would have wanted in the first place. As we study his images along with the scientific publications that have followed, we are encountered with evidence that continues to inform public consciousness. Biology has already answered the question of when human life begins for us, and Nilsson’s work provides visual evidence.

“…in considering the question of when a new human life begins, we must first address the more fundamental question of when a new cell, distinct from sperm and egg, comes into existence,” states Dr. Maureen Condic, Associate Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Utah School of Medicine and the Director of Human Embryology instruction for the Medical School. We can follow up with Dr. Condic’s statement, by examining Nilsson’s photography of the embryo only a few weeks after fertilization. (Condic 3)

“ Just a few weeks after fertilization, primitive nerve cells…are visible in a human embryo…some parts of the brain receive only sensory impressions from the body, such as sensation and pain, while others are responsible for vision and hearing…others movements…” (Nilsson 78)

New cells are prolifically being created, but as Dr. Condic’s observations further state, “Human embryos from the one-cell (zygote) stage forward show uniquely integrated organismal behavior that is unlike the behavior of mere human cells. The zygote produces increasingly complex tissues, structure and organs that work together in a coordinated way. Importantly, the cells, tissues and organs produced during development do not somehow “generate” the embryo…they are produced by the embryo as it directs its own development to more mature stages of human life.” (Condic 4)

“When week 5 begins, the embryo changes rapidly. Within just a few days it is transformed from a clump of cells into an oblong body, with a head and a tail beginning to take shape around the neutral tube.” (Nilsson 76) Evident in the photograph titled, Fetus, 13 Weeks, the human life has a fully formed head, brain, eyes, ears, arms and legs.

I have an early ultrasound image of my oldest son, (now 32), at 18 weeks sucking his thumb in the womb. Unlike Nilsson’s famous image, my son was alive in my womb. It is critical to note, however, that both images show biological evidence of a human being at this very stage in their life. K.V Turley describes Nilsson’s image as follows: “Perhaps this is nowhere more the case than in the image of an unborn child approximately 18 weeks old, contentedly sucking its thumb while apparently asleep in its mother’s womb. Studying the photograph more closely, one sees the child’s hands are fully formed; its nails are clearly visible, its eyelids are closed, its face at peace. Even today, half a century after the photograph was taken, there is a gentle beauty about the image that is difficult to define. Unquestionably, this is in part due to the universal awe felt at the mystery of life incarnated during a pregnancy. Doubtless, however, it is also due to the powerless dependency of the child in the picture. … All the more poignant still as it is claimed that these children in particular were late-term abortions from a Stockholm clinic.” (Turley)

There has been controversy and discussion in regards to the fact that many of the embryos “scientifically” documented by Nilsson were of the aborted. During the years he spent photographing the unborn, Nilsson also went as far as reaching out to medical facilities performing abortions in order to obtain more subject matter for his work, though the images published in LIFE came primarily from the Stockholm clinic. As stated poetically and tragically by K.V. Turley, “…it is sobering to realize that our journey to life was contemporary with that of the unborn children whose images remain encapsulated forever in a child is Born, but whose own passage to life, as it turned out, was truncated. That haunting image of the unborn child sucking its thumb is ultimately a photograph record of its subject’s life story complete” one as beautiful as it was tragic.” It is interesting to note that the composition of the images published in the 1965 issue of LIFE have been targeted for their composition by abortion supporters claiming that the seemingly floating embryos move the viewer to see the fetus as an individual, apart from its mother. (Julich S.) The photographs of the embryos, however, were purely scientific in nature and presented by Nilsson purely as studies of the “unseen”. The dark negative space in which a few of the images seem to “float” in, provides a sense of the mystery of the womb moving us to realize the fact that an individual is forming and growing. The purpose of the uterus, which exists solely in the biological female body for the purpose of supporting another separate, individual life, is clearly evident in this ground-breaking photographic essay.

The work of Lennart Nilsson provides intrinsic evidence of how the arts can and have informed public discourse and consciousness. Photography and science have been partners in the humanities since photography was documented as a “scientific discovery” by Niepce in 1839. From the study of nature, both the visible and invisible we are presented with documents of the world around us and the life within us. Evidence of the miracle of life is readily available for us to look at. The question that remains is, how will we continue to respond?

About the Author

Belenna Mesa Lauto is currently a professor of photography at St. John’s University in New York. Her work has been widely exhibited throughout the United States and also internationally in Spain, France, Columbia and Argentina. Her work aims to invite contemplation of the self in both the physical and spiritual realms. Via https://www.belennalauto.com/.

Bibliography, Citations

Condic, Maureen. “A Scientific View of When Life Begins.” Charlotte Lozier Institute, Lozier Institute, 4 Aug. 2017, lozierinstitute.org/a-scientific-view-of-when-life-begins/.

“Fetus, 18 Weeks | 100 Photographs | The Most Influential Images of All Time.” Time, Time, 100photos.time.com/photos/lennart-nilsson-fetus.

Jacobs, Steven. “Biologists’ Consensus on ‘When Life Begins’.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 25 July 2018, pp. 1–22., doi:10.2139/ssrn.3211703.

Jansen, Charlotte. “Foetus 18 Weeks: the Greatest Photograph of the 20th Century?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 18 Nov. 2019, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/nov/18/foetus-images-lennart-nilsson-photojournalist.

Jülich, Solveig. “Picturing Abortion Opposition in Sweden: Lennart Nilsson’s Early Photographs of Embryos and Fetuses.” DIVA, 25 Mar. 2017, www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1084538.

“Midwife in the Mountains.” Midwife in the Mountains | Lennart Nilsson Photography, www.lennartnilsson.com/en/a-life-of-stories/midwife-in-the-mountains/.

Nilsson, Lennart, et al. A Child Is Born. 5th ed., Bantam Books Trade Paperback; Penguin Random House LLC, 2020.

Turley, K. V. “You’ve Seen the Photos-Now Here’s the Story Behind Them.” NCR, 3 Nov. 2017, www.ncregister.com/blog/you-ve-seen-the-photos-now-here-s-the-story-behind-them.