OTH Talks to Helen Shenton, College Librarian at Trinity College Dublin

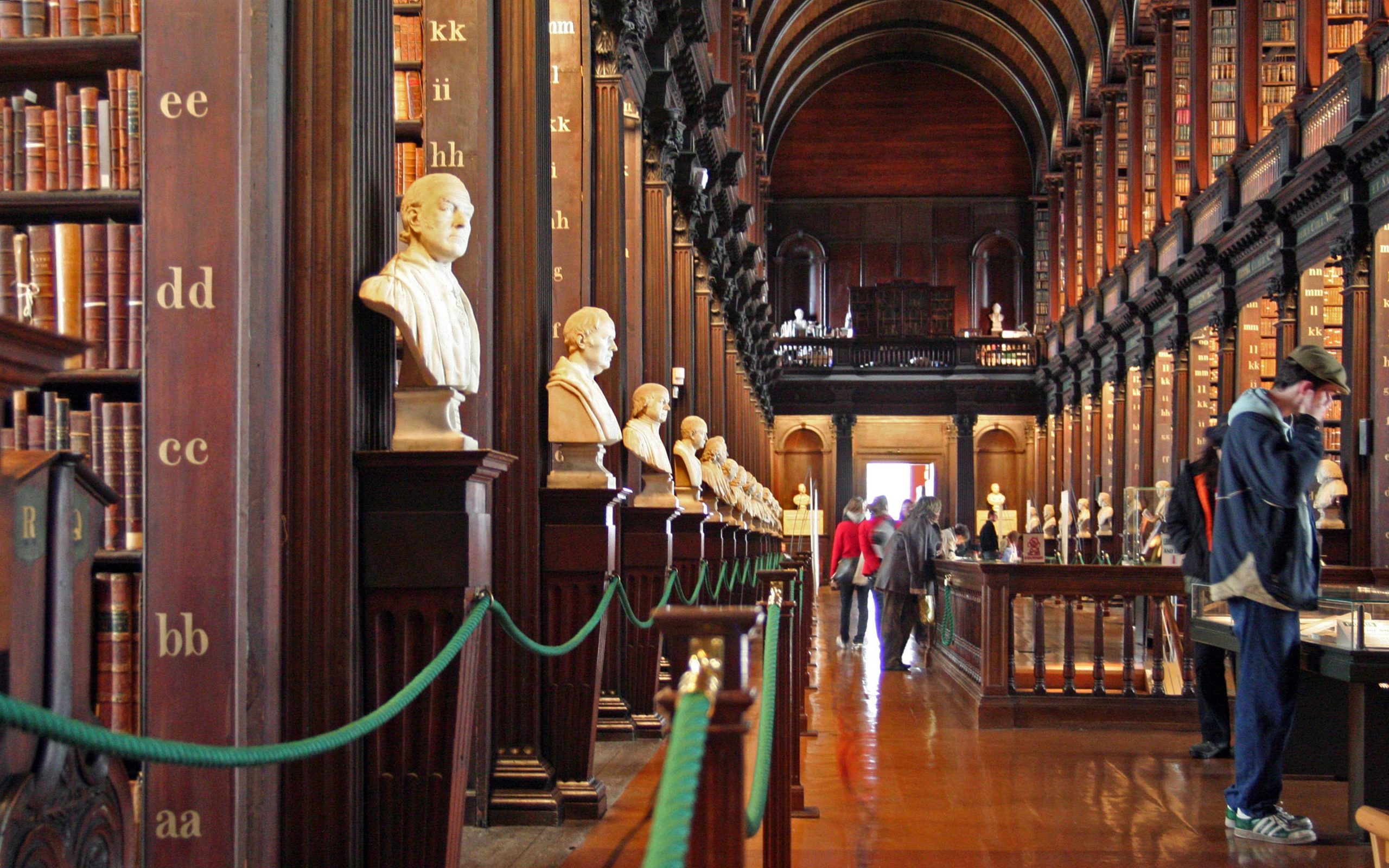

The Old Library at Trinity College Dublin is famous around the world as the home of the Book of Kells. It also houses 40 sculpture-busts of scholars and other luminaries like William Shakespeare. When it was decided to add sculptures of women scholars, the women now represented were selected from nominations by students, staff, and alumni.

The four women now represented in the Long Room are scientist Rosalind Franklin, folklorist, dramatist and Abbey Theatre founder Augusta Gregory, women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft and mathematician Ada Lovelace. The artists commissioned were Vera Klute, Guy Reid, Rowan Gillespie and Maudie Brady. The new sculptures are the first to be commissioned for the Long Room in the Old Library in more than a century. The ceremony of unveiling the new Trinity College sculptures took place on February 1, 2023, St. Brigid’s Day, a new public holiday. The first Irish public holiday named after a woman, St. Brigid’s Day acknowledges the unique role that women have played in Irish history, culture and society.

Oh, the Humanities! recently talked to Helen Shenton, Librarian and College Archivist at Trinity College Dublin, about the process of selecting the women scholars and the artists who created their sculpture busts. This interview has been slightly edited for clarity and length.

Clare Doyle (OTH): Tell me a little bit about the process of shortlisting the artists. Was it delayed by COVID and the lockdowns?

Helen Shenton (Trinity College Dublin): We shortlisted nine artists and we invited them to choose two of the women scholars and to create maquettes. We paid for the maquettes, which I think during COVD was particularly good, because, as you know, everyone was so concerned about the welfare of artists. So, no, it was a long process, but COVID didn’t really slow us down.

Clare: That’s great. And the nominations of the women scholars—that was a process where you reached out to staff and students and a broader community than just a small select committee?

Helen: We invited all nominations—we had hundreds of nominations—from anyone. And it wasn’t along the lines of who got the most votes or anything, We then had very robust discussions as to who should be chosen, and our one criteria is that we wanted two women from the arts and humanities, and two from the STEMs.

Clare: That’s great, yes—that struck me that you had a nice balance between women in their different fields. Was there any pushback from people who said, for instance, “Oh, these choices were great, but there should have been three out of the four women who were Irish”, or anything like that?

Helen: No, the criteria were really very broad. We didn’t say anything about nationality—it was women scholars who were deceased. That was all it was. And since we announced them, we haven’t had any pushback as such. People have said, “Oh, I championed so-and-so,” but no, there hasn’t been any pushback as to who we chose. Lady Gregory is the most connected with Ireland, but that wasn’t part of our criteria. We wanted international scholars.

Clare. That’s very interesting, and rather appropriate too, perhaps, for our post-COVID world.

Helen: And if you look at who all the male scholars [in the Library] are, everyone from Cicero to Swift to Hamilton, that’s very broad. We actively wanted to be broad.

Clare. Yes, interesting point, nobody ever said, “Oh, these men aren’t all Irish!” So, was there anyone that surprised you, from the nominations? “Oh, I’ve never heard of that woman before?”

Helen: Throughout the whole process, we all learned so much. There were names that I wasn’t particularly familiar with, and we discussed them, so I learned about those women. I’ve learned a huge amount about who these women were. We had an event the following day, the day after St. Brigid’s Day, a conversation between the four artists, and I had four Trinity scholars champion each of the women. Oh my Lord—they were so insightful—it was riveting. That will be online soon, we’re just editing the film of it. Again, everyone in the room learned something about the individual scholars. And it was fascinating coming at it from the point of view of our academics, who had been inspired personally and professionally, in their fields. But then the artists–I moderated it, and I was expecting them to talk about their response in terms of materials and technique, but they’d researched [the scholars] so much that they had become experts as well, and knew about times in their lives and how that reflected incidents in the artists’ own lives. The whole thing has just been a journey of learning and discovery.

Clare: Yes, I noticed when reading the article on your website that gave more details about each sculpture that each artist was tailoring their technique to the career and the personality of the woman. It was really interesting to get that insight into the techniques of sculptors, which you don’t always get.

Helen: Yes, and we’ve taken films of the artists in their studios, The artists were two women, two men—two Irish, two Continental European. We captured their creative process, which was really important, and they’ve talked about their choice of materials. All the previous sculptures were marble, some of them were Carrera marble, Two of the sculptors did choose marble, and one is lime wood, beautifully carved lime wood from the upper reaches of the Alps. And Rosalind Franklin’s is composed of different materials; there’s Parian, a type of porcelain, and there’s Jesmonite for her jacket, which is very textured, and then there’s Swarovski crystals for the necklace, and that’s a reference to the X-Ray crystallography that she used in her research that led to DNA. That actually contributed to her death, because she had been exposed to hundreds of hours of X-Ray crystallography, and it struck me, actually, that three out of the four women all died at 37 or 38.

Clare: That’s pretty startling, that three of the four were so young. It’s a great initiative. A little history–Am I correct in thinking that women as students were admitted into Trinity College at the beginning of the 20th century?

Helen: 1904, and that followed about 12 years of campaigning and petitions and so on, but it was 1904.

Clare: So a little over a hundred years. I haven’t tracked down a copy yet, but there is a book that focuses on the history of women in Trinity College, “Troublemakers” or something like that [The book is A Danger to the Men? A History of Women in Trinity College Dublin, 1904-2004, by Susan M. Parkes, Lilliput Press, 2004].

So it sounds as if a lot of work went into the campaign. Are there plans to add any more sculptures? The article mentioned bringing more diversity to the public spaces of Trinity College. Are there plans in general or specifically for the library?

Helen: I’ll address the library aspect of that if I may. It took quite a while and a lot of people and resources to pull off, and we wanted in particular—as you know, the Long Room is closing at the end of this year for major conservation. So I felt it was very important to get [the sculptures of the women] in beforehand. And with [the new public holiday] St Brigid’s Day, that became the obvious day to do the launch. So they’ll be in [the Library] for almost a year. Then our focus will be very much on this major, once-in-a-century conservation. I obviously aspire to getting more in there, but we’ll have to see how we go about doing that. But there’s definitely overall a desire to have more diversity, more representation of diversity in general across the campus. You probably know about the fabulous portrait of Mary Robinson [Chancellor from 1998-2019} that’s in the Dining Hall. That’s similar to the sculptures in some ways in that you don’t notice [the preponderance of male portraits] necessarily when you walk into these spaces, it’s not glaring, but when you get your eye in, you see this major difference. So that’s the direction we’re traveling in.

Clare: That’s great, thank you so much. I think our subscribers are going to find this very interesting, especially in the context of Women’s History Month but also with St. Patrick’s Day coming up.