by Professor Elizabeth Kuipers

She tip-toed to her place in the wings, outside of her boss’s office, waiting for her cue—the silence of the end of a phone call. Her stomach churned. Her audience could react, embrace her expression of vulnerability or reject her completely.

The dress rehearsal happened on Friday. She thought that her audience would be responsive, even though they were not face to face. She thought that her questions were reasonable. She simply asked for clarification. She needed to know before she committed to the year-long run what the terms of that commitment were. She got no response.

So, she rehearsed all weekend. The next performance would be so much easier, in her zone of comfort, if it could be in writing. But writing is dangerous. Writing can be documented. Writing can be forwarded. Writing can be damning. The rehearsals wore her out—the constant play in her mind. The constant “What if?” The knowing. The knowing that she was being screwed again. That she was worth more. And yet, knowing that she dare not wish for too much. There were stakes. There were children to feed. There were college educations to pay for. And she was expendable to her employers.

The twenty years she worked in her first job out of graduate school taught her she was expendable. The moves to all of the dances were ingrained in her very being. When her students’ eyes lit up with understanding, she felt the energizing joy and beauty of a perfectly executed stag leap across the stage. She worked her craft, practicing, tweaking, getting a little higher, a little farther each time. The perfect leap represented hours upon hours of practice, calloused feet, bruised knees, but the light in the students’ eyes was worth it every time! The Charleston, gay and careless, was not as gay or as careless as it seemed when the Women’s Studies Faculty did it to bring attention to violence against women, when we bit off the ends of our figurative, phallic cigars and spit them in the faces of the entirely male administration who didn’t want a spectacle. She learned the Shuffle too, head down, avoiding eye contact, watching her feet, when she was denied promotion by her colleagues who had worked with her for fourteen years, hearing her voice echoing down the close hallway as she taught her heart out, but who still said they weren’t “assured” that she was an excellent teacher. She knew to save the Tango. The Tango was for when she couldn’t look away, when the dictate from on high was so egregious that she not only withstood the tension of the dance, but invited it, hoping that someone would be there to catch her when she got spun out of the hands of the men in charge. Always the men in charge.

Those years taught her to shape-shift, to be pliable. Her Can-Can sounded like Yes. Of course. I will. I’ve never done that before, but I’ll give it my best. She re-made herself to fit the needs of the department, the needs of the students. Everyone’s needs…It’s not that she was unappreciated. Every few years she would get a card or an email from a student who remembered her fondly. When she was unfulfilled, wrung dry from continuously learning new steps, she learned dances in other places, always hoping to be the change she wished to see in the world.

The constant “What if?” The knowing. The knowing that she was being screwed again. That she was worth more. And yet, knowing that she dare not wish for too much. There were stakes. There were children to feed. There were college educations to pay for. And she was expendable to her employers.

When she left for what she thought to be a more compelling cause—creating a new place for children to learn in a community handicapped by years of poverty and despair—no one noticed. No one told her goodbye. No one thanked her for 20 years of loyal service in higher education. For her 30s. For her 40s. She was expendable. But her children were worth it, she said. The children of the community were worth it. This new environment would be filled with love, respect, and equality. The teachers would be creative, and the children and parents would be engaged and involved. This school would help to change the future for thousands of children, parents, and members of the community. Children would learn about service and civic pride and would be equipped to soar to any height they imagined. She envisioned a Contra-dance, full of noisy, upbeat music, communal, giving and taking in turn. Yet men continued to play the same tune, the one she had learned to Shuffle to. As she shuffled, more and more slowly, moving down into a depth she had never dreamed, men struck absurd poses on stage, fueled by their egos, pomposity, and fear. No amount of money could compensate for the soul-crushing loss of her dream.

Feeling the failures of the past in her knees and in her heart, she executed a plie into the chair, her chin high, attempting to exude grace and courage she did not feel. She fumbled her way through the first steps.

She explained to her boss, “I need you to understand why I responded the way that I did. Maybe it’s being 50. I’m not willing to feel taken advantage of anymore. “

In her mind, she twirled on her right pointe shoe, her left leg soaring high in an attitude as she stood up for what was right, what was fair.

“The job that is a ‘promotion’ will mean more work, more stress, but no more money. There is gender inequity at play. The new hire, a boy straight out of graduate school, with a lower teaching load, is making more than I am.”

Her ankle wobbled.

“I would be angry all of the time. That would not be fair to anyone here.”

Her boss reached out to her—steadying her pose—saying, “I appreciate your candor.” How far does that steadying hand extend? Will it extend through the impromptu meeting? Through turning down the insulting gesture at a promotion which her boss facilitated? Will it extend to contracts for next year?

She left the office, knowing that her dance had been shaky. Her words were disorganized, but she stayed true to herself.

Within minutes she had another performance, this time for a very different audience. A ballet would shut them down completely. The pandemic made the audience exceptionally small: two Black male teenagers furtively studied their phones as she explained epic similes. The others, purportedly streaming the class, were undoubtedly playing video games or listening to music because every time she called on one of them, she got no response. She could execute the opening to Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” but in the current climate, these students might take that as an insult from a middle-aged white woman rather than an effort to cross the divide. No, these students didn’t want Michael Jackson. In fact, they didn’t want anything she had to offer them; today’s offering was “The Iliad.” She felt like Prince Humperdink reading signs in the dirt: “There was a mighty duel….” Even the impressive choreography of Inigo Montoya and the Dread Pirate Roberts couldn’t thaw this small group of students. Homer’s pearls before swine. Circe would be proud. They endured. She endured, hopeful that the next class would be more engaged.

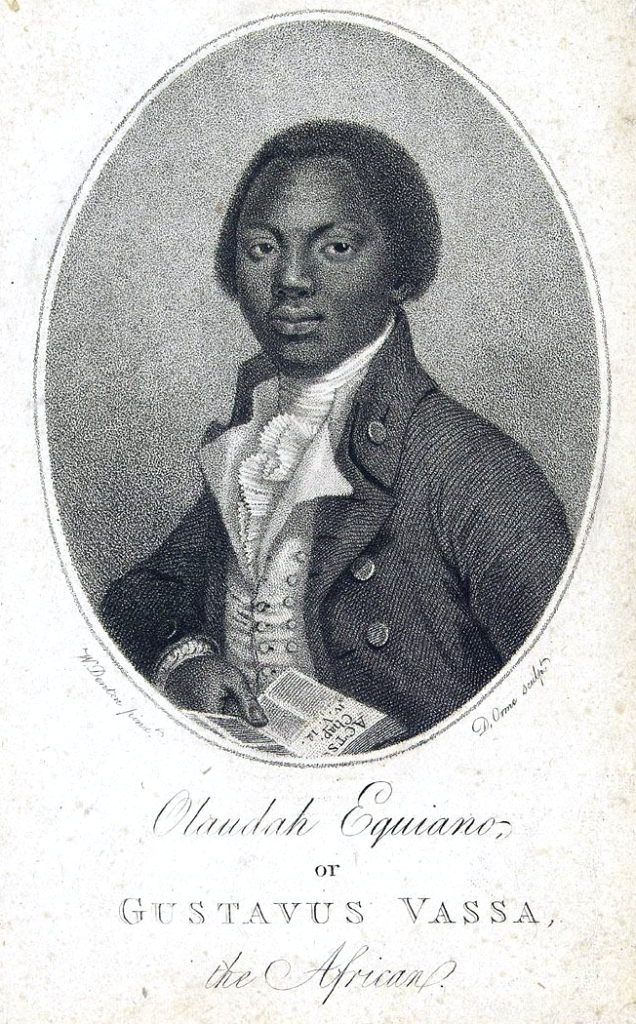

“The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or Gustavus Vasa, the African, written by Himself.” These tickets should be easy to sell, she thought. A story of life in Africa, kidnapping, enslavement, the Middle Passage. It’s eighteenth century HipHop. A man claims himself and defies the odds. It’s edgy; it’s truth revealed. Certainly the students who chose to go to a Historically Black College would be engaged, maybe even excited. Two young women arrive on time, one perpetually on her phone and the other hiding behind her computer. Thirty minutes into class, two young men come in, one completely empty handed, the other with a pencil and spiral notebook through which he shuffles trying to find a blank page. With ten minutes of class remaining, she gets their attention with the question, “How do we dehumanize people now?” She leads them by the nose, connecting the dots: slaves were dehumanized to legitimate atrocities against humanity; after 911, Muslims were dehumanized to increase fear and legitimate a war; Trump used tear gas on peaceful BLM protests for a photo-op at his convenience and a platform of “law and order.” How much has changed, she asks as she steps hopefully out onto her right pointe shoe, leg poised to elevate, but never coming off the floor.

“The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or Gustavus Vasa, the African, written by Himself.” These tickets should be easy to sell, she thought. A story of life in Africa, kidnapping, enslavement, the Middle Passage. It’s eighteenth century HipHop. A man claims himself and defies the odds. It’s edgy; it’s truth revealed. Certainly the students who chose to go to a Historically Black College would be engaged, maybe even excited. Two young women arrive on time, one perpetually on her phone and the other hiding behind her computer. Thirty minutes into class, two young men come in, one completely empty handed, the other with a pencil and spiral notebook through which he shuffles trying to find a blank page. With ten minutes of class remaining, she gets their attention with the question, “How do we dehumanize people now?” She leads them by the nose, connecting the dots: slaves were dehumanized to legitimate atrocities against humanity; after 911, Muslims were dehumanized to increase fear and legitimate a war; Trump used tear gas on peaceful BLM protests for a photo-op at his convenience and a platform of “law and order.” How much has changed, she asks as she steps hopefully out onto her right pointe shoe, leg poised to elevate, but never coming off the floor.

After class, she has an existential crisis. She knows that she is not truly educating these students. Her arms shoot out at jarring angles from her body. She has no idea how to make them care. She kicks to the left, throwing her head back aggressively. She is not even sure if they can read the homework that she assigns. She collapses her body into a fetal position. But this inability is not their fault; instead it is the fault of a system that has failed them. On her feet again, she punches the air. This is a modern dance. It is abstract; Isadora Duncan be damned! There is no language for this disservice or the hopelessness she feels on behalf of her students and herself. This dance breaks the rules of the system that leaves 85% of the children behind….the poor, the ethnic other, the desperate…those who don’t know any better. She stomps her feet and waves her arms over her head with abandon. So the haves cut the Federal School Lunch Program for the have-nots who then are incapable of learning because they are hungry and can’t focus on their school work. She circles as if the floor is on fire, never leaving one foot in place for long. Projections for prison populations are based on the number of students who are unable to read on grade level in the third grade! She channels the mother of Equiano who undoubtedly expressed her own grief at his kidnapping in a violent dance around a blazing fire. If only she could convince her students to dance this dance with her! She, they, we all can claim ourselves!

She is quickly exhausted by the movement and the emotion. This dance is unsustainable.

She drives home, an hour of quiet on country roads. Her spirit settles. Her equilibrium returns when she sees her home and knows she is blessed. She is in a different realm. No physical needs go unmet. She has a dear husband and sons who love her unequivocally. She has books to sustain her imagination. All is well. She can rest.

The usual exchanges happen when she walks in the door. “Hey, Mom!” a boy yells. The pandemic has stranded them at home. They work online with pre-recorded lessons taught by a variety of teachers for each subject. There is no connection. There is no desire to please these individuals who, in normal times, would turn into her sons’ away from home support system, their champions. There will be no letters of recommendation for college scholarships from these teachers.

She replies cheerfully, “Hi! How was your day? How did your schoolwork go?” The usual answers follow. On a whim, she adds, “Bring down your computers and let me see what you’re up to.”

The air immediately fills with tension. The freshman’s face registers something….concern? fear? Her dances are not done for the day. Worries about how to choreograph this dance before she even knows what to call it fill her mind.

She is not a parent who yells. But when she sees fifty-two missing assignments in English, thirty-four in science, forty-six in math, all she can think is, “Not you too! Another child lost and dishonored by this combination of forces that feels out of control.” But this is her child; she cannot lose him. She must execute the perfect dance or the tragic outcome will be of her own design.

She reaches out to him with a brush step, hearing the front of her tap shoe slide softly against the floor. “What in the world is going on?” she asks with direct eye contact. She must bring him into the dance.

“I don’t know,” he responds.

“Do you never work?” She begins to tap out a tentative rhythm. He responds with a shoulder shrug. “Do you work at least a little every day?” She knows he must be allowed to riff on his own, but he doesn’t seem to know the steps. There are consequences for not knowing the steps of this basic dance.

“Bring me your phone and your game controller.” Step-ball-change away from him. He Shuffles away. She knows that dance so well it breaks her heart to see him do it.

When he returns and hands her his technology, she does the buffalo shuffle towards him, saying, “Tomorrow, you will come to work with me and sit in my office to get caught up.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

She grabs his chin, holding it firmly, asserting the rhythm of her heart into his cheeks and saying, “I love you. Even when I’m mad at you I love.” His eyes tell her that they can be in sync soon. She must keep dancing.

Alice Walker says that hard times require furious dancing. These are hard times. She longs for Baby Suggs to step off the page of Beloved and call her community into a dance. To call the women in, crying; to invite the men to begin the dance; and to bring in the little children laughing in spite of the hard times. In community, the dance will morph and include all, creating space for those who need to cry and those who need to laugh, here if nowhere else. Only in a true community can she find solace and healing. So. She will keep dancing, inviting her students, her friends, and her family to join her, hoping that in the dance she can empower others to keep true to the rhythms of their hearts.

About the Author

Elizabeth Kuipers’s love of teaching began in the 70s when she cajoled her little brother into completing “homework” which she promptly graded with a red crayon. Years later, at Wesleyan College, the first college in the world chartered to grant degrees to women, Elizabeth learned to love the written word and to be a fierce feminist. An MA and PHD in English later, she committed to public education where she has lead a team to design and open a K-12 charter school and worked in administration in both K-12 and higher education. But she has consistently found her way back into the classroom where her heart will remain.

Elizabeth Kuipers’s love of teaching began in the 70s when she cajoled her little brother into completing “homework” which she promptly graded with a red crayon. Years later, at Wesleyan College, the first college in the world chartered to grant degrees to women, Elizabeth learned to love the written word and to be a fierce feminist. An MA and PHD in English later, she committed to public education where she has lead a team to design and open a K-12 charter school and worked in administration in both K-12 and higher education. But she has consistently found her way back into the classroom where her heart will remain.