by Ernest Young

Introduction

This article is a comparative view of social justice of Benjamin Banneker’s (1731-1806) “Letter to Thomas Jefferson” 19 August 1791, the reply “Letter to Benjamin Banneker”, 30 August 1791, the “Declaration of Independence” 1776 by Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826); “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” 1852 by Frederick Douglass (1817-1895) and” Ain’t I a Woman?” 1851 by Sojourner Truth (1797/-1883).

LaGarrett J King’s article, “More Than Slaves…” argues that “Throughout the mid-18th to mid-19th Centuries, Black Founders helped establish Black institutions, served in the military, developed Maroons settlements, and used media to openly challenge and critique the practical ideas of democracy” (p.88)

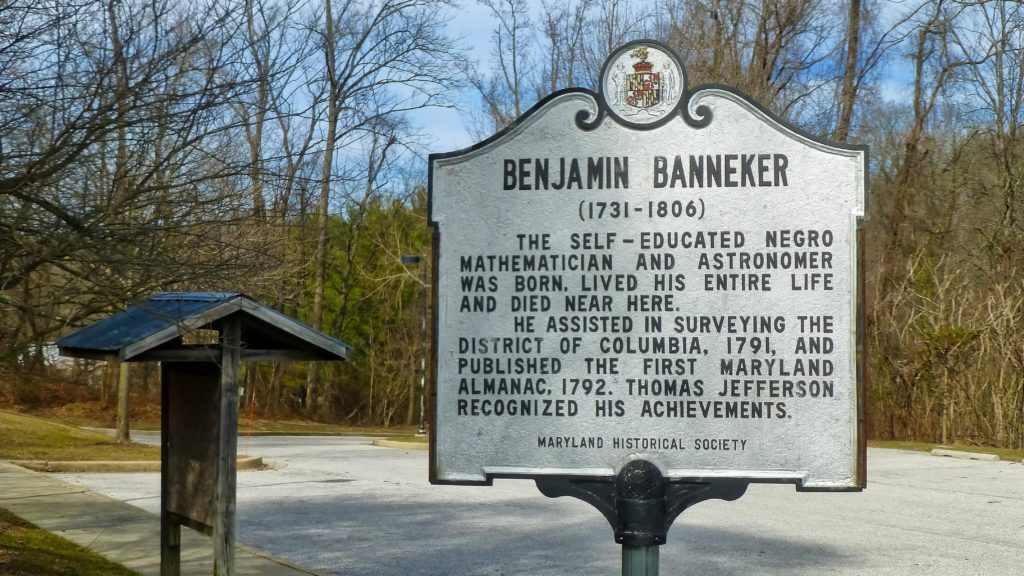

Benjamin Banneker, the African American Astronomer, Almanac writer, Mathematician and Surveyor, wrote on Thomas Jefferson expressing his views on slavery. He uses moral suasion to reason with Jefferson on the issue of equality. He writes:

“Now sir, if this is founded in truth, I apprehend you will embrace every opportunity, to eradicate that train of absurd and false ideas and opinions, which so generally prevails with respect to us… (p 1)

He cites biblical references; paragraph eight (8) “put your soul in their souls’ stead;” Job 16:34, and James 1:17 “every good and perfect gift is from above”, challenging Jefferson to see the injustice of slavery, and the justice/rightness of freedom for all. He reminds Jefferson in paragraph seven (7) of the words from the “Declaration of Independence” written by Jefferson; “we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…”

Charles Cerami’s book, Benjamin Banneker: Surveyor, Astronomer, Publisher, Patriot (2002), asserts that Banneker is a courageous free African American intellectual who dares to challenge Secretary of State Jefferson regarding slavery. If Jefferson is persuaded by Banneker to denounce slavery, then Jefferson would become a strong proponent in support of Banneker’s cause against slavery.

Scholar, Angela G. Ray’s article “In My Own Handwriting” notes, “By sending the letter and manuscript copy of the almanac together, Banneker constructed himself rhetorically as a free man, as one capable of bestowing gifts” (p. 400)

Jefferson’s reply to Banneker:

“Nobody wishes more than I do, to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren talents equal to those of the other colors of men… (p 1)

Jefferson’s reply to Banneker is a polite platitude. He dodges the issue because Banneker is proof.

Additionally, Thomas Jefferson became a United States Diplomat, Secretary of State, author of the Declaration of Independence and the third President of United States.

Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence:

“Governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed… (p. 1)

According to Jefferson, the government’s role is to protect individual rights and promote the general welfare of those for which it is charged to govern.

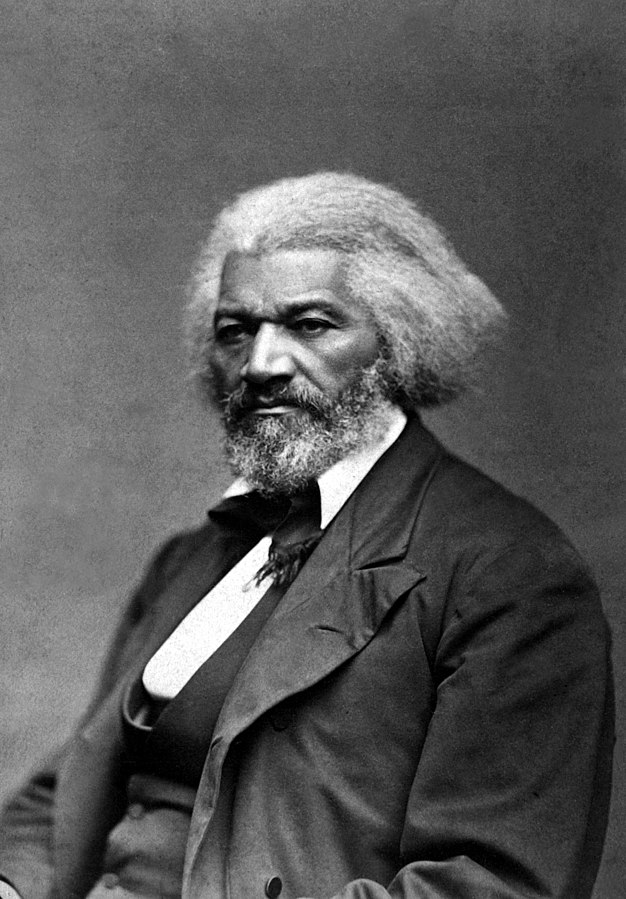

Next, Frederick Douglass, an African American Abolitionists, Diplomat, Orator and Newspaper publisher/writer was born a slave but fought and won his freedom. Therefore, he is very adamant about the cause of freedom and liberation for all slaves.

Douglass delivered “What to the American Slave is the 4th of July?” as part of an 1852 Independence Day Celebration at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York.

“What to the American slave is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. (p. 9)

Douglass, a former slave, knew the slave’s feelings and thoughts about this 4th of July commemoration. How can slaves celebrate freedom and liberation when, in fact, they are yet slaves and have never experienced freedom and liberation?

Duffy and Besel’s article “Recollection, Regret, and Foreboding in Douglass’s 4 of July oration of 1852 and 1875”, argues that.

“Douglass maintains that the Fugitive Slave Law essentially nationalized slavery. The law made it possible for an African American man living in the North to be consigned to slavery in the South… “(p. 10)

Douglass biblical references states:

“This to you is what the Passover was to the emancipated people of God.” (p,2)

The Biblical Passover reference chronicles the Israelite’s deliverance form Egyptian bondage (slavery).

“And the blood shall be to you for a token upon the houses where ye are and when I see the blood, I will pass over you…” Exodus 12: 13

In another Biblical text he compares the British government’s tenacious hold on the colonies to Pharaoh’s dominant oppression of the Egyptians.

He writes: “But, with that blindness which seems to be the unvarying characteristic of tyrants, since Pharaoh and his host were drowned in the Red Sea, the British Government persisted in the exactions complained of.” (p. 3)

“And the waters returned, and covered the chariots, and the horsemen, and all the host of Pharaoh that came into the sea after them; there remained not so much as one of them.” Exodus 14: 28

The use of Biblical quotes by Douglass demonstrates his awareness of the United States religious heritage since its inception.

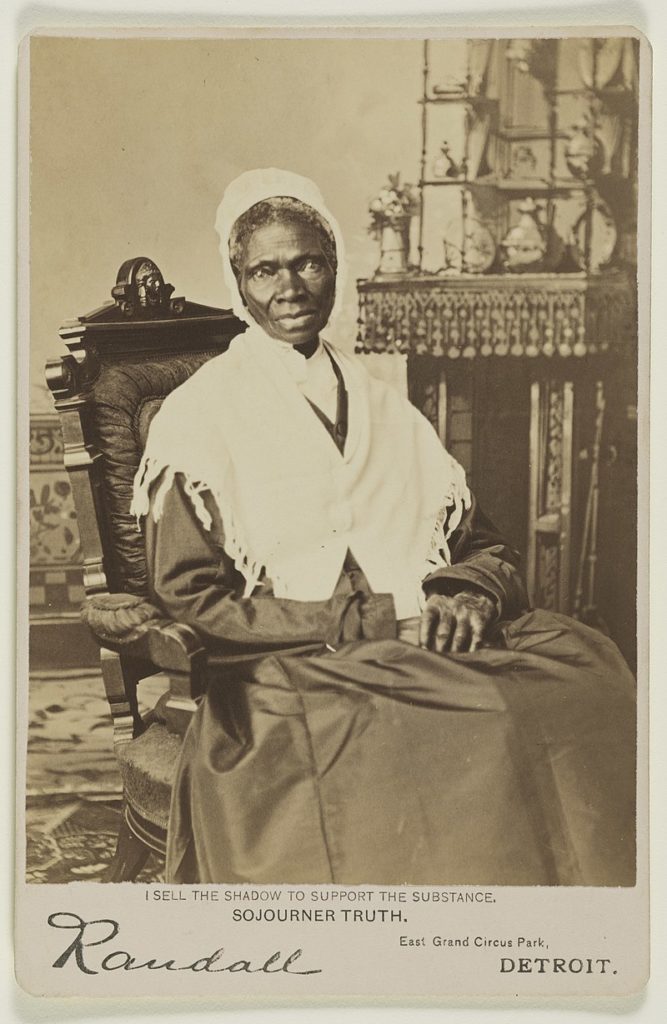

Finally, Sojourner Truth, an African American female Abolitionists, Missionary and Orator was bilingual and spoke the Dutch language. She was born a slave but fought and won her freedom. In her speech “Ain’t I a Woman”, delivered in Akron, Ohio, on May 28-29, 1851, Truth makes the case that women are oppressed as slaves are oppressed. She was relentless in challenging white women regarding all women’s rights. Scholar, Meredith Minister’s article: “Religion and (Dis)Ability in Early Feminism” posits:

Finally, Sojourner Truth, an African American female Abolitionists, Missionary and Orator was bilingual and spoke the Dutch language. She was born a slave but fought and won her freedom. In her speech “Ain’t I a Woman”, delivered in Akron, Ohio, on May 28-29, 1851, Truth makes the case that women are oppressed as slaves are oppressed. She was relentless in challenging white women regarding all women’s rights. Scholar, Meredith Minister’s article: “Religion and (Dis)Ability in Early Feminism” posits:

“In this speech, Truth’s references to her black, female body challenged religious discourses that regarded women as weak and susceptible to temptation and cultural discourses on “true womanhood… (15-16).

Truth states:

“Den dat little man in black dar, he say women can.t have as much rights as men, cause Christ wan’t a woman! Whar did your Christ come from?” From God and a woman! Man had nothin’ to do wid Him.

If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women togedder ought to be able to turn it back, and get it right side up again! And now dey is asking to de it, de men better let ‘em.”

These statements by Truth are so profound as they resonate in many circles of liberation today.

She also used Biblical references in her speech.

“Now the birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise: When as his mother Mary was espoused to Joseph, before they came together, she was found with child of the Holy Ghost.” Matthew 1: 18, 21

“If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone…”

“And when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree to be desired to make one wise, she took of the fruit thereof, and did eat, and gave also unto her husband with her; and he did eat.” Genesis 3:6.

Frederick Douglass said it best about Truth when he eulogized her in Washington in November 1883. He said:

“Venerable for age, distinguished for insight into human nature, remarkable for independence and courageous self-assertion… (Russell, 1998, p. 419).

Conclusion

Benjamin Banneker, Frederick Douglass, and Sojourner Truth are the embodiment for social justice against oppression. Thomas Jefferson wrestled with, and it was not clearly settled as to his views on slavery. They challenged the world with their lives and their words for justice and truth.

LaGarrett King argues that attention to “Black Founders” illuminates the “intellectual agency” that African Americans exercised throughout the history of the United States”. King writes:

“Such agency explores the philosophical and practical approaches to how Black Americans responded to racialization and the limited citizenship opportunities in the United States… (89).

Also, they left a powerful legacy of commitment to justice. May their contributions challenge us to continue this commitment?

Works Cited

Banneker, Benjamin, “Letter to Thomas Jefferson” 19 August. 1781 Direct Link

Charles Cerami, Benjamin Banneker: Surveyor, Astronomer, Publisher, Patriot (2002)

Douglass, Frederick, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” 1852. My Bondage and My

Freedom, New York: Druer, 1969 441-5 1852

Duffy, Bernard K. and Richard D’ Besel, “Recollection, Regret, and Foreboding in Douglass’s

Fourth of July Orations of 1852 and 1875”. Making Interdisciplinary Approaches to Cultural

Diversity 12.1 (2010): 4 -15.

Jefferson, Thomas. “Letter to Benjamin Banneker 30 August 1791 Direct Link

“Declaration of Independence” 1776.: Direct Link

King, LaGarrett J. “More Than Slaves: Black Founders, Benjamin Banneker, and Critical

Intellectual Agency”. Social Studies Research & Practice 9.3 (2014): 88-105.

Minister, Meredith, “Religion and (Dis)ability in Early Feminism”. Journal of Feminist Studies

in Religion, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2013. p. 5-24.

Ray, Angela G. “In My Own Handwriting: Benjamin Banneker Addresses the Slaveholder

of Monticello”. Rhetoric & Public Affairs, 1.3 (1998): 387-405.

Russell, Dick. Black Genius and the American Experience. Carrol & Graf. New York, 1998.

Truth, Sojourner, “Ain’t I a Woman” (1851) Direct Link

About the Author

Ernest Young earned a BA degree, U. of California, Santa Cruz, an M Div., Iliff School of Theology, a D. Min., Claremont School of Theology. Currently. he is a Ph.D. candidate, Union Institute & University. Also, he is a Humanities Instructor with the Los Angeles Community College District.