by Kevin Eamon Muehleman

Background

South Africa was the first country in the world to prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation, which was included in both the 1993 Interim Constitution and the 1996 Constitution. Section 9 of the Constitution, known as the Equality Clause, explicitly provides South African citizens with constitutional protection from discrimination on the basis of their sexual orientation, stating that:

“The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.”[1]

This was a progressive feat for the country, marking its claim as the most gay-friendly destination throughout the African continent. In 2006, South Africa became the fifth country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage and is still the only sub-Saharan African country today that provides legal status and protections to same-sex relationships.[2]

The progressive legal environment in South Africa is in stark contrast to other African nations that have colonial-era laws that criminalize homosexual behavior and where some offenders can face the death penalty.[3] In fact, of the 69 countries that criminalize same-sex relations throughout the world, 33 are in Africa.[4] However, the legal protections for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, and asexual ( LGBTIQA+) in South Africa have not always aligned with conservative communities within the country. Even with strong, progressive legal protections, many members of the LGBTIQA+ community in South Africa continue to battle violence and discrimination in their everyday lives.

LGBTIQA+ Asylum Seekers

LGBTIQA+ individuals who experience bigotry in their own country look to South Africa as a safe haven because of its progressive policies and legal protections. This has led to a high number of LGBTIQA+ asylum seekers fleeing their homes and seeking out a better life where they can express themselves authentically. However, many LGBTIQA+ asylum seekers have found that South Africa has not been the most welcoming as they thought. A 2021 report from Legal Resources Center found that asylum officers unlawfully discriminated against LGBTIQA+ asylum seekers, denying their applications to enter the country although they met the criteria to seek “protection under international and domestic law.”[5] The report found that 67 applicants who applied for asylum on the basis of their sexual orientation or gender identity were wrongly denied between 2010 and 2020. The officers were also found to display hostility and bigotry toward LGBTIQA+ applicants through the use of derogatory language and use of stereotypes about sexual and gender minorities. The report found that some officers were “unaware that sexual and gender minorities constitute a protected social group under the Refugees Act.”[6]

Gender-Based Violence

South Africa also faces systemic gender-based violence (GBV) throughout the country. GBV is disproportionately directed against women and girls and is also experienced by those who do not conform to their assigned gender roles. A 2016 report by Love Not Hate found that 11% of LGBTIQA+ youth (ages 16 to 24) reported experiencing rape or sexual abuse at school, and 31% of lesbian and bisexual women experienced sexual violence.[7] The South African government has developed a National Strategic Plan to address GBV and continues to revise its policy and approach to combating violence in the country.[8] The current president, President Cyril Ramaphosa, has recently vowed to strengthen the country’s laws on this issue. He has promised to address legislative gaps and fast-track new laws, among other recommendations.[9] However, critics have also expressed concern over the lack of funding for shelters and other services for victims and that more should be done to protect marginalized groups, including sex workers, the LGBTIQA+ community, and undocumented people.[10]

Education

Policymakers and activists have used education as a tool to bring further awareness to issues affecting the LGBTIQA+ community. According to the same Love Not Hate report, 56% of LGBTIQA+ South Africans aged 24 years old or younger expressed they had experienced discrimination based on their sexuality or gender identity in a school setting.[11]

South African grade schools are moving toward including LGBTIQA+ policies and education in their classrooms, programs, and curricula. The Department of Basic Education (DoE) developed a guidebook in 2017 for schools to teach gender identity and sexual orientation to grade-school children throughout South Africa. The goal is to ensure schools are more inclusive and supportive of their LGBTIQA+ students by upholding the values set in the Constitution.[12] In 2019, the DoE developed plans to overhaul school textbooks in order to make them more inclusive of same-sex families and sexual and gender minorities. The department found that LGBTIQA+ people were referenced twice in the 38 textbooks in nine subjects.[13] In 2020, the Western Cape DoE drafted South Africa’s first gender identity and sexual orientation guidelines in hopes to develop more inclusive and supportive environments for LGBTIQA+ students.[14] [15] These initiatives aim to lay the groundwork needed to develop inclusive policies, like gender-neutral bathrooms, dress codes, participation in school sports, and combat bullying.

However, all of the policies have faced backlash from conservative and religious groups and politicians who believe that children should not be taught about LGBTIQA+ inclusion in the classroom. Freedom of Religion South Africa encouraged parents to withdraw their children from schools “in the event that it conflicts with their own value systems.”[16] One politician, Rev Kenneth Meshoe, president of the African Christian Democratic Party (ACDP), said that he intends to fight the government’s “wicked” plan to treat “masturbation, gender nonconformity, and single parent families as a mainstream.”[17] Additionally, far-right Christian groups from the United States have poured over USD 56 million to fight against LGBTIQA+ rights and access to safe abortion, among other issues, throughout Africa.[18] This outside influence has contributed to further polarization over gender and sexuality issues in South Africa.

Research and Methodology

Throughout my four-week stay in South Africa, I chose to further examine the country’s policies and laws that aim to protect this population. Through formal and informal interviews and conversations with policymakers, educators, and members of the LGBTIQA+ community, it become apparent that the country’s laws were not always enforced equitably and fairly. All too often, LGBTIQA+ people experienced discrimination and tremendous obstacles to the rights that they were supposedly granted by the Constitution. There seems to be a great disparity between the policies and how they are implemented throughout society. I conducted interviews and conversations with individuals without explicit content to publish their interviews. Therefore, I have chosen to keep their identities anonymous. Most of the interviews lasted one hour in length and were held in Pretoria, Johannesburg, Mbombela, Mamelodi, and Cape Town.

Department of Basic Education

I corresponded with a representative in the Social Mobilisation & Support Services at the Department of Basic Education to discuss their office’s work in ensuring LGBTIQA+ students received the resources and support they needed. The representative has shared their office’s work on developing manuals and guidelines that were discussed earlier in this paper, including the Constitutional Values and School Governance and Dealing with Homophobic Bullying.[19] [20] They acknowledged the difficulties in incorporating the materials into all schools throughout the country.

University of Pretoria (UP)

UP is unique that it allocates multiple resources toward LGBTIQA+ inclusion and education. From academic to student-led initiatives, the campus has programs and support groups for students to embrace their identity and learn more about the community.

I met with a representative at the Centre for the Study of AIDS and Gender (CSA&G) at UP. They shared how the center was founded in 1999 to guide the university’s response to HIV prevention tactics. Today, CSA&G collaborates with nine faculties across the UP and has expanded its work in social justice, GBV, leadership and advocacy, and community engagement.[21] They highlighted concern that traditional STEM fields, like medicine and engineering, were less likely to interact with CSA&G, as compared to the humanities and social sciences. For example, they shared the story of a recent Zoologist student who was undergoing their transition from female to male. The student was able to have support from faculty members, staff, and the administration to ensure they were able to use the name and pronouns of their choosing. However, they have not been asked to facilitate such a scenario at the engineering school, although they are sure students in the field would benefit greatly from resources provided by the center. They are working to build stronger relationships with that department. They are also in the process of updating UP policies to ensure further support for transgender and intersex students.

I also corresponded with a representative at the Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Expression, and Sex Characteristics (SOGIESC) Unit at the Centre for Human Rights at UP. This unit is housed with the School of Law and aims to “advocate for and work towards equality inclusion non-discrimination, non-violence, and non-heterosexism” for LGBTIQA+ persons. [22] The unit’s work focuses on influencing policies and laws to ensure the rights of sexual and gender minorities throughout Africa. Students are able to take workshops, participate in mock trials, and conduct legal research on issues affecting LGBTIQA+ individuals.

I also met with two undergraduate students who identify in the LGBTIQ+ community. They shared more information about the two LGBTIQA+ student-led organizations on campus: 1) Up and Out, and 2) Queer Space Collective. Up and Out is a social organization that builds community and programming for the LGBTIQA+ community.[23] The Queer Space Collective is a social group that uses creative writing as a tool to make UP “safer and more inclusive of queer identity and expression.” [24] Both groups organize social and professional events for students, including sexual education workshops and PRIDE events.

I also had an informal conversation with two UP students who did not identify in the LGBTIQA+ community. The two young, Black men were born and raised in a township nearby and are 20 years old. When asked if they supported gay rights, the men expressed that they had their own “problems”, which they described as wanting to start a family and starting a successful career after graduation. They both added that they have “nothing against” LGBTIQA+ people, but that they didn’t feel the need to advocate for their rights and protection when they are dealing with their own concerns about their future in South Africa.

I consulted the use of the concept “problem” with my professor who shared that the concept is used in a South Africanism context and is a translation from local languages to mean different things. For instance, “I have no problem” could mean “I accept”, and “I have my own problems” could mean many things as well.

University of Mpumalanga (UM)

UM was established in 2014 and represents a very, rural community in Mbombela. During my day-long visit, I met with a professor whose research focuses on gender disparities and LGBTIQA+ experiences. They shared their work in making UM a more inclusive and accepting campus. Specifically, they explained the difficulty they’ve experienced in incorporating gender-neutral bathrooms throughout new campus buildings. UM recently constructed new buildings but decided to exclude gender-neutral spaces. They have been working with the administration to understand how this decision was made and what can be done to ensure spaces are incorporated in future projects. They also highlighted the high demands placed on themselves as the only dedicated faculty that focuses on gender and sexual identity at the university. Additionally, that professor serves as the faculty advisor for the student-led organization, The Conscious Youth Foundation (CYF), which aims to combat gender-based violence and promote inclusive policies for sexual minorities. They connected me with three students, all identify as Black or Coloured, who are founding members of the organization. We met over lunch to discuss their work with CYF and their personal experiences within the LGBTIQA+ community.

CYF started in 2021 as a way for students to get involved in voicing their concerns about the growing problem of GBV in the country and to support the LGBTIQA+ community on campus. The students explained how many transgender people, especially those who were assigned male at birth, experience backlash and often violence. Within the last year, CYF has promoted programming and events specifically tailored toward visibility for the LGBTIQA+ community. Students organized social events during PRIDE celebrations, including a fashion show and parade. Students commented that most members of the community supported the events, or at least they were not vocal against the events happening. Students did not receive protestors or other opponents who aimed to shut down the events. The students also expressed their satisfaction with UM administration who supported the group’s effort to host the events.

One of the students identifies as a lesbian and considers themself a “tomboy” who dresses in traditionally masculine clothing. They shared the backlash they received from family members and childhood friends who believe they need to “try dating men” and dress “more appropriately.” Another student shared their experience of coming to terms with identifying as gay. They have recently come out to close friends but have not shared the news with family, who they fear will not accept them due to strong religious beliefs. All three students expressed their desire to move to Johannesburg after they graduate from UM. They all view Johannesburg as a more welcoming place for LGBTIQA+ people, both socially and professionally. They do not expect to live in Mbombela again, although their families have settled down in the region.

Beaulieu College (BC)

I conducted an informal interview with a teacher at Beaulieu College, a co-educational private boarding school in Midrand, Johannesburg, with English instruction. The total annual fee for a 12th grader is R 147,363, which equals USD 8,980.[25] Notably, this is near the “average household net-adjusted disposable income per capita” in South Africa, which is USD 9,338 a year according to OECD.[26] The teacher supports the Diversity and Inclusion Program at BC. They shared how the school has implemented progressive policies, including gender-neutral bathrooms and gender inclusion in sports. They also shared how three transgender students were supported during their transitions by teachers, staff, and the administration. The students were able to use the pronouns and names of their choosing and were allowed to dress in the uniform of their gender identity.

Ikamvayouth

I visited the Ikamvayouth Center in Mamelodi, which provides after-school sessions and programs to grade school students, including academic tutoring and psycho-social support.[27] I had many informal conversations with students from grades 9 – 12 as I helped tutor them in algebra and life sciences. During this discussion, two Black male students shared their views on LGBTIQA+ people. They mentioned that a few of their classmates identified as gay or lesbian and that they personally had “no problem” with it. They acknowledged that some of their peers were verbally bullied for identifying within the LGBTIQA+ community, but that a majority of their classmates had “no problem” with gay people. Again, the students shared a similar sentiment that being gay was “not my problem”, which could very well mean they accept this community. The students also shared that they were more focused on getting an education and having a successful career.

Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action Trust (GALA)

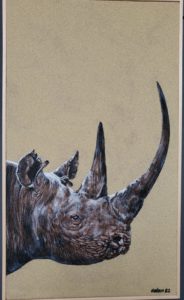

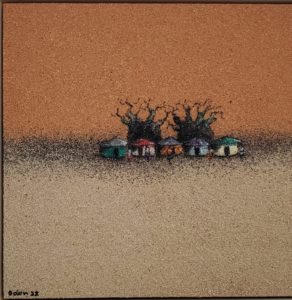

I met with a representative of GALA, a nonprofit organization that works for the “production, preservation and dissemination of information about the history, culture and contemporary experiences of LGBTIQA+ people in South Africa.” [28] GALA operates a community library, facilitates educational workshops, and organizes queer art exhibitions. They shared their belief that greater awareness about the experiences of individuals would bring more acceptance in society.

Conclusion

South Africa has made great strides in developing policies and laws that aim to protect the most vulnerable, marginalized populations. However, implementation is a different story. The country has received fair criticism from domestic and international advocates and researchers for the inequities in policy implementation and enforcement. There is a great discrepancy between the policy’s intention and how it is actually implemented and carried out in society. The most privileged members of society– those who have access to private schools, urban settings, family support, and progressive healthcare facilities– tend to fare well in terms of gender and sexual identity, expression, safety, and economic prosperity. Urban settings seem to have more resources and acceptance toward gender and sexual minorities, while rural environments face more challenges in accepting LGBTIQA+ individuals.

Policymakers have made lofty promises over the years to increase support for the LGBTIQA+ community, but have a long way to come to ensure they uphold the ideals set forth in the Constitution. Still, South Africa has the benefit of having a tangible document, the Constitution, that clearly lays out the ideals of the nation. It is a physical reminder that sexual orientation is a protected class in society. Many countries throughout the world lack the same legal acceptance of LGBTIQA+, which sets South Africa apart as one of the most accepting countries around the world.

Education has become a strong tool used by advocates in the country to ensure acceptance and support for LGBTIQA+ individuals. Education can be used to dispel harmful stereotypes and viewpoints toward the LGBTIQA+ community. From my interactions, it seems that young people are willing to share their stories in hopes to live their most authentic lives, even when it counters the beliefs they grew up in. Visibility is crucial in order to change perceptions and create a more inclusive and equitable society in the future.

Work Cited

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Section_Nine_of_the_Constitution_of_South_Africa

[2] https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9408/

[3] https://www.amnesty.org.uk/lgbti-lgbt-gay-human-rights-law-africa-uganda-kenya-nigeria-cameroon

[4] https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/06/22/progress-and-setbacks-lgbt-rights-africa-overview-last-year

[5]https://law.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/PDFs/Promise/Annual_Symposium/2022_Symposium_SOGI/LGBTI%2B%20Asylum%20Seekers%20in%20South%20Africa.pdf

[6] Ibid 5.

[7]https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/Impact-LGBT-Discrimination-South-Africa-Dec-2019.pdf

[8] https://www.justice.gov.za/vg/gbv/NSP-GBVF-FINAL-DOC-04-05.pdf

[9]https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-assents-laws-strengthen-fight-against-gender-based-violence-28

[10]https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/11/24/south-africa-broken-promises-aid-gender-based-violence-survivors

[11] Ibid 7.

[12] http://section27.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Chapter-9.pdf

[13] https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1037969X20986658

[14] https://pmg.org.za/call-for-comment/936/

[15]https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/412351/proposed-guidelines-for-schools-in-south-africa-include-unisex-bathrooms-dress-code-and-lgbtq-support/

[16]https://www.mambaonline.com/2019/05/14/uproar-over-lgbtiq-inclusion-in-south-african-schools-textbooks

[17] Ibid 16.

[18] https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/africa-us-christian-right-50m/

[19]https://www.academia.edu/13202415/Values_in_Action_A_Manual_in_Constitutional_Values_and_School_Governance_for_School_Governing_Bodies_and_Representative_Councils_of_Learners_in_South_African_Public_Schools#:~:text=The%20values%20are%3A%20quality%20of,%2Dsexism%3B%20ubuntu%20and%20governance.

[20]https://www.education.gov.za/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=YVvGE_K6SR0%3D&tabid=625&portalid=0&mid=2180

[21] https://www.csagup.org/what-we-do/

[22] https://www.chr.up.ac.za/sogiesc-unit

[23] https://www.facebook.com/UpandOutTuks/

[24]https://www.up.ac.za/faculty-of-law/news/post_2515546-invitation-queer-space-collective-launches-queer-africa-2-at-the-university-of-pretoria

[25] https://beaulieucollege.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/KS-2022-Fee-structure-1.pdf

[26] https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/countries/south-africa/

[27] https://ikamvayouth.org/about/our-programme/

[28] https://gala.co.za/about/history/