by AC Panella

A question sometimes asked to help folks reflect on their gendered experiences something similar to, “Do you remember the first time someone asked you to change your behavior, clothing, or language because of your gender?” This question intends to evoke a memory of feeling for folks who may not have thought about their gender in an examined way. The answers to this vary; experiences from toys and imaginary play to being asked to change clothes to ‘something more appropriate’ or something similar.

Whatever the answer, these memories are important. First, they are interactions that may have encouraged or discouraged or complicated our understanding of how our bodies move in the world. Second, remembering this interaction may have a ripple effect on our understanding of the social practices that come around gender as a society. Finally, something makes them worth remembering. With the myriad of gendered interactions, one has been exposed to and chosen or needed to forget; memory may start to outweigh impact in daily life more than policy regulations or social policing of gender. Memory functions as the historian for gendered practices. Gender, then, as a concept is a mnemonic device for both regulating and remembering in a gendered world.

Mnemonic devices are more than word play for remembering and retelling information; a mnemonic device can be any system that uses recollection to quickly use complex information. Gender as it’s currently invoked in a U.S. context tends to function to quickly recalling the complex histories of bodies and the expectations those bodies. Gender as a mnemonic device is a complex response to colonial and binary concepts of gender, it is the remembering, forgetting, and responding to memories regarding gender within a collective social group.

Gender & Memory

Reformulating gender as a mnemonic device builds in the multi-sensory understandings of gender and may offer new forms of interruptions that expand the legitimacy of different gendered knowledges and practices. For gender to function as a mnemonic device, we must understand the development of social memories and how to create interruptions and reposition gendered memory from the personal to the ideological.

A mnemonic device is an artifact or system to help remember elements or qualities of a particular moment. For example, you may have learned “Every good boy does fine” to learn the lines on the music stave. Or “my very easy method just set up nine planets” to learn the order of the planets, back when we still considered Pluto a planet. These are mnemonic devices intended to quickly recall a particular kind of academic fact. Mnemonic devices used to capture experiences, memories, or short cuts to understanding. Souvenirs are tangible objects to remind of place experience, photos capture an emotional moment, and, in society, identity categories function as a short cut to understanding the complicated histories and emotions an individual may have experienced because of their connection to social groups.

A mnemonic device is an artifact or system to help remember elements or qualities of a particular moment. For example, you may have learned “Every good boy does fine” to learn the lines on the music stave. Or “my very easy method just set up nine planets” to learn the order of the planets, back when we still considered Pluto a planet. These are mnemonic devices intended to quickly recall a particular kind of academic fact. Mnemonic devices used to capture experiences, memories, or short cuts to understanding. Souvenirs are tangible objects to remind of place experience, photos capture an emotional moment, and, in society, identity categories function as a short cut to understanding the complicated histories and emotions an individual may have experienced because of their connection to social groups.

This last quality of identity may help others and ourselves remember our own notions of that particular identity. When limited to binary definitions a gender, a person may remember ‘what it means to be’ a man or woman. However, gender in its current form of mnemonic device is insufficient for representing the range or experiences of a great deal of people. This is why trans (at its broadest definition) challenges a collective memory of gender¹. The tidy framework of binary gender doesn’t offer a way to reframe gender within the embodied memories of an individual.

Susan Stryker, author of Transgender History notes, “Because most people have great difficulty recognizing the humanity of another person if they cannot recognize that person’s gender, encounters with gender- changing or gender-challenging people can sometimes feel for others like an encounter with a monstrous and frightening unhumanness.” One reason for this difficulty in recognition, is not being able to have a recall device that challenges one’s ability to enact social practice. Without this device a person may have a destabilizing response to experiencing gender based on a recollection of what gender “should be” or “used to be.” This mnemonic practice needs to be rewritten if we are to engage with everyone’s humanity.

Art & Memory

Art is one intervention to mnemonic practices. Art can capture and reposition gender in a material and visual way. We can see how image works to captures and reiterate those gendered memories. Sometimes in more impactful ways than direct education or interaction. For example, we are more likely to remember The Last Supper as depicted in the painting, than we might reading the thick description in The Bible. This is one type of short cut to remember a part of a religion. Art by trans folks breaks this mnemonic practice because it invokes trans memory and gives insight to how gendered memories are preserved and passed on in public.

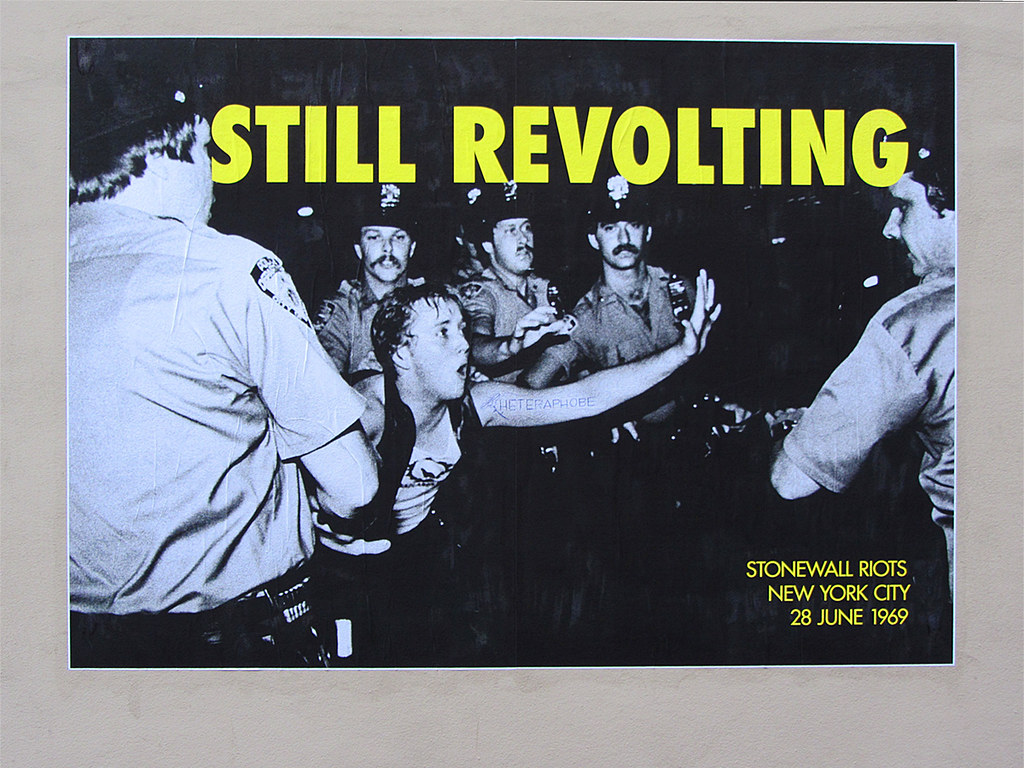

When this is looked at on a group level, collective memory can be a way of quickly passing on and remembering important information across that shared experience. Memory can be shared through such practices as building physical monuments, holidays, or ceremonial traditions. For example, in the LGBTQ community, June is marked as LGBTQ pride month. Events, statues, and historical landmark designations have been created to honor the memory of the Stonewall Uprisings. This captures an important social turning point. Sharing the story of Stonewall through movies, artwork, and memorials can help in understanding a historic moment and may demonstrate how a collective has shifted.

Memories, like Stonewall, become similar to a document that has been copied too many times. The original image gets incredibly dulled or distorted the more it’s copied. Collective memory is shaped through this process with each new monument, individual interpretation and reproduction. Today there is a democratization of knowledge and memory because of technology, social media, and other projects of globalization. When it comes to gender, trans people are gaining access to seeing and learning about trans histories, mythology, and memory.

These memories for trans people can inform and validate identity; highlighting the complicated ways gender as a concept reinforces oppressive social structures based on patriarchal and colonized thought cementing binary gender as a memory construct. There is a myriad of trans artists who tackle trans history, futurity, and memory in their work. Chris Vargas, Nicki Green, and Vick Quezada are trans identified artists who challenge the way memory functions through interrogating institutionalization, religion, and biopolitical systems of gender. Their work contributes to material interruptions of gendered mnemonic practices.

One of the most commonly displayed works of Chris Vargas’ is The Museum of Trans Hirstory. A traveling exhibit, it uses real and created objects to codify moments of trans history. Objects include Sylvia Rivera’s high heel, signs from bars, and a mug from Compton’s cafeteria. Vargas says of this installation:

“Stories of gay and lesbian civil rights victories like the dissolution of sodomy laws, the creation of employment nondiscrimination protections, and gay marriage all tend to trace back to rebellion, while the critical role that transgender women, many of color, played in these advances has slipped deep into unseen corners of historical memory” (99).

What Vargas produces shines a light to that “unseen corner of historical memory.” He connects trans lineage by displaying tipping points in trans history. These objects both memorialize trans experience and elevate its importance by positioning them within a historical institution. Vargas’ work inspires us to rethink how we might ‘trans’ art and museum space to reflect the vast array of genders their memories.

These memories for trans people can inform and validate identity; highlighting the complicated ways gender as a concept reinforces oppressive social structures based on patriarchal and colonized thought cementing binary gender as a memory construct.

Museums are one way culture institutionally transfers gendered information; religion is another. Deeply connected to memory, religion often invokes gender in ritual thus preserving it in a collective memory. Nicki Green recreates artifacts related to gendered religious traditions through ceramics and sculpture. There are many Jewish traditions that Green has been excluded from because of her trans identity. She has recast ritual objects centering a trans feminine perspective; recognizing that the memory of these objects is layered and complicated across gendered experiences. As she says,

“I’m interested in the bedikah cloth because it’s a material way of recording the body. I recognize this practice and other ritual related to the regulation of women’s bodies can be and have been traumatic for many who participate. As a trans woman, I have this distance from these rituals because my body is not halakhically or historically included in these traditions, and that distance allows me the privilege to repurpose them in a way the feels empowering” (406).

By repurposing ritual practice to be inclusive of trans experience, Green offers trans people a pathway to reconnecting and rethinking rites of passage and celebration within Western spiritual practice. Of note is that it is a Western colonized spiritual practice; there are a variety of indigenous practices that have capaciousness for genders beyond the binary.

Artist Vick Quezada critiques colonialism by centering their art around indigeneity and on colonialist rewritings gender. They describe their work saying,

“Plants, like humans, can be queer; they, too, are assigned genders. In terms of my work, gender is not always explicit, but it’s certainly embedded. I am the maker so I bring myself everywhere I go, right? But my critique of settler colonialism is consistent throughout my work. The structures created by Western colonial ideologies are the same ones that create systemic oppression and control gender constructs” (np).

Through their work, Quezada demonstrates how nation states codify and reinforce what gendered expectations should be. Often pulling from and erasing indigenous resources.

These artists show how gender is a shorthand for societal expectations, historical knowledges, and predictive mechanisms for desire and connection. Gender as a memory device, highlights the ways we reinforce and distribute power and privilege in our society through placing emphasis on gender expectations. Trans people undermine this mnemonic practice by inhabiting multiple perspectives, creating new gender identities and challenging religious and social traditions that are tied to gendered expectations. To trans gender is to make new mnemonic devices for understanding and inhabiting bodies.

Conclusion

People with trans identities and practices defy gender as a mnemonic device because rather than relying on historic social memory, gender practices are individualized and reinvented. These practices may be ignored throughout time because memory of a binary gender system is so strong. Consistently exposed to mnemonic devices that reinforce binary gender and not challenge it; this process is built through a combination of social practice and capitalist governmental forces. We check boxes, create policy, and build environments that all reinforce historic practice of gender making it nearly impossible for trans people to find themselves in space, history, or memory in public practice. Trans activist Marsha P. Johnson has said, “History isn’t something you look back at and say it was inevitable, it happens because people make decisions that are sometimes very impulsive and of the moment, but those moments are cumulative realities.” Our world can reflect our vast human experience and interrupting binary gender systems through artistic intervention is a way to reflect and share each new iteration.

Notes

- For this conversation, I’m defining trans as the actions and embodiment of people who do not use their gender assigned at birth to dictate their social expectations regarding tradition and desire. This can include transgender, non-binary, and gender expansive communities. This is a type of trans practice rather than a limited trans identity. For the sake of brevity, I’ll be using the term trans throughout the rest of this article but please know it’s not as an intention to obscure or erase these experiences but rather to encompass those identities and practices.

About the Author

AC Panella is a trans Ph.D. candidate in the Humanities at Union Institute and University. He has worked on a variety of projects including the Trans Leadership Academy, The LA Trans Health Coalition, and this year developing the Trans Oral History Project in conjunction with Georgia State University. His research is focused on trans collective memory and history as it’s represented in visual and material culture. When he isn’t nose deep in research, he is a full-time teacher, pet parent, and truncle (Trans-Uncle) to a super adorable three-year-old.

Feature Photo Credit: Ted Eytan via Flickr