by Sophia Boutilier

What’s the problem with microaggressions?

What makes microaggressions such a big deal? Aren’t they, by definition, micro in nature? Microaggressions are every day, routine, even unintentional, slights and exchanges that denigrate or single out individuals because of their group membership (Barthelemy et al 2016, Sue et al 2007). They are often ambiguous, subtle, and challenging to pinpoint (Jones et al 2017). Consequently, microaggressions end up as the quiet burden to bear of the people who are targeted (it’s just too much work to explain it to people who don’t get it), overlooked by others (who don’t get it), and left unchecked (because those in power can’t comprehend the problem). Yet this oversight directly contributes to the repeated incidence of microaggressions, a violence which is compounded by its invalidation as ‘no big deal’ by people who don’t have to experience it (a microaggression in itself!) (Sweet 2019).

The concept of death by a thousand cuts comes to mind, particularly if the doctor you went to see told you that you weren’t *really* bleeding. And it’s this insidiousness, this ability for microaggressions to fly under the radar of managers and supervisors, that makes them hard to diagnose and contributes to the perception that the aggressed are overreacting, hyper-sensitive, irrationally angry, or whining (Ahmed 2021, Jones et al 2017, Orelus 2013). The inability of members of the dominant group to identify a microaggression when it happens and to recognize the long line of similar slights to which a particular insult is just one more instance that further isolates the person coping with the aggression (Orelus 2013). Such an institutional environment makes reporting difficult, often protecting aggressors and causing targets of microaggressions to question their own perception of reality (Barthelemy et al 2016, Jones et al 2017, Solorzano 1998). It’s no wonder that repeated microaggressions negatively impact work performance for individuals on their receiving end and reinforce harmful and prejudicial stereotypes for the wider community (Sue et al 2007, Solorzano 1998).

What do they look like?

Because microaggressions can be difficult to spot from the outside, it is imperative to collect the stories and experiences of the people who experience them (Barthelemy et al 2016, Solorzano 1998). For example, three-quarters of women in a physics graduate program, a typically male-dominated field, experienced microaggressions including sexist jokes, sexual objectification, the assumption of their inferiority, as well as being ignored, passed over, or treated as invisible in their work environment (Barthelemy et al 2016). Although these instances were three times more common than “outright” or hostile sexism, women who reported sexist behavior were encouraged to overlook it or were ignored by supervisors. The denial of sexism dovetailed with the idea of science as neutral and having a ‘culture of no culture’, obscuring and perpetuating the ways women are sidelined in the field (Barthelemy et al 2016, Harding 1986, Des Jardins 2010). These women’s experiences are not isolated or unusual. They are common to male-dominated fields like STEM fields and speak to more general patterns of exclusion (Funk and Parker 2018).

A few other examples of microaggressions include:

- Complimenting a scholar of color for being articulate as if it’s surprising that they are well spoken (Orelus 2013);

- Assuming that people in fat or bigger bodies are unhealthy and/or being surprised that they are healthy or physically active (Gay 2017, Gordon 2021, West 2017);

- Ignoring, interrupting, taking credit for, or downplaying the contributions of minority colleagues (Solorzano 1998);

- Assuming that women or people of color know everything there is to know about women and people of color, and relying on them to educate others (Orelus 2013);

- Asking a prospective female employee of childbearing age or who is currently pregnant what her “plans” are (Kitroeff and Silver-Greenberg 2018);

- Referring to a male colleague as “assertive” while the same behavior by a female colleague is labelled as “loud” (Correll 2017);

- Having lower expectations of minority students or co-workers (Solorzano 1998);

- Asking someone who is not the visible norm where they are from (Wing et al 2007)

Why do they matter?

Experiencing the inconsiderateness of a colleague is of course not limited to the experiences of minorities. Anyone can be on the receiving end of rudeness (Fleming 2019). In contrast, microaggressions are chronic, repeated instances of deep social divisions. Although they might seem small, one-off events, situating them in a historical and contemporary context reveals longstanding patterns of discrimination (Solorzano 1998). By way of particularly stark example, both female scientists and university professors, and graduate students of color, report being treated like ‘second class citizens’ who didn’t belong in their institutions (Barthelemy et al 2016, Orelus 2013, Solorzano 1998). In both cases this treatment is rooted in a history where members of these groups were not just treated as second class citizens, but actually were second class citizens and accordingly denied human, civil and legal rights (Orelus 2013). In other words, microaggressions are simply the tip of an iceberg of historically and socially entrenched animus from which minorities endure a steady drip.

The concept of death by a thousand cuts comes to mind, particularly if the doctor you went to see told you that you weren’t really bleeding.

Despite their name, microaggressions have *macro* effects. Targets of microaggressions are more likely to experience symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (Berg 2006). In the face of routine slights and dismissals, women and people of color report constantly having to prove themselves at school and work and facing higher penalties for making mistakes than their colleagues (Madsen et al 2015). Consequences include reduced performance, lower satisfaction, and higher rates of burnout for individuals (Krivkovich et al 2018, Jones et al 2017, Martell et al 1996), as well as reduced profits, innovation, and productivity for organizations (Ferrary 2013, Funk and Parker 2018). When organizational norms and leadership fail to prevent microaggressions, their cultures discourage diversity and place an unfair burden on minority groups to cope silently with the stress of discrimination ((Jones et al 2017, Orelus 2013). Often these aggressions fail to meet legal thresholds for discrimination, leaving targets vulnerable to repeated abuse, and even contributing to the fiction held by some that racism and sexism are no longer common problems (Ferber 2012).

What can be done?

Discriminatory cultures are dynamic and interpersonal products which include targets, perpetrators, bystanders, and allies—all of whom have roles to play to change a biased climate (Jones et al 2017). More space needs to be made for marginalized groups to identify microaggressions and access channels to hold aggressors accountable (Barthelemy et al 2016). Shifting the culture to take seriously the experience of the person feeling aggressed, regardless of the intent of perpetrators is essential to challenge gaslighting and invalidation and to prevent aggressions before the point that reporting needs to take place (Applebaum 2010, Oluo 2017, Sweet 2019). Incentives and accountability can reduce the social costs associated with reporting (Sue et al 2017), especially in ambiguous situations which are both more common and harder to pinpoint (Shelton and Stewart 2004, Correll 2017). Restorative paradigms that emphasize addressing the harm rather than adjudicating if a policy was violated can reduce the adversarial nature of reporting and associated retaliation (Ahmed 2021, Hamad 2020, Wemmers 2017). Establishing dialogue and group problem-solving may also reduce barriers as research shows that women who have experienced bias are more likely to recognize bias directed at other women than directed at themselves (Jones et al 2017). Bringing employees together to share stories and solutions is often more effective to identify microaggressions than leaving targets to speak up for themselves individually (Summers-Effler 2002).

Even when targets call out racism, sexism, and other forms of prejudice, reporting will only work if aggressors can listen to and believe their colleagues and appreciate their experience of the exchange. This should also include equipping privileged persons (regardless of their history of perpetration) with the tools to deal with defensiveness, fear of being wrong, or disappointment that might result when they learn they have, perhaps unwittingly, participated in bias against a colleague. Bystanders may be effective at intervening and sanctioning the perpetrator, but such action does not guarantee higher levels of acceptance toward the target (Jones et al 2017). A multi-pronged approach is necessary. Training and actions for acknowledging and interrupting implicit bias (Perry et al 2015, Yen et al 2018) and revising workplace conventions for bias that may be ‘baked in’ (Correll 2017) are also important. The latter could be transformed through equitable and transparent distribution of opportunities and tasks, and intentional review of how work is assigned and evaluated (Blickenstaff 2005).

About the Author

Sophia Boutilier is a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at Stony Brook University. Her research focuses on the international development industry, inequalities, and social justice. She is particularly invested in scholarship that engages privileged groups to challenge their dominance in support of social change. In addition to her academic work, Sophia has authored policy documents on gender inequality and sexual violence prevention. She draws inspiration from her field experience as a development worker, and from the writing of critical race and feminist theorists.

Work Cited

Ahmed, S. (2021). Complaint!. Durham: Duke University Press.

Applebaum, B. (2010). Being White, Being Good: White Complicity, White Moral Responsibility, and Social Justice Pedagogy. Washington DC, Lexington Books.

Barthelemy, R. S., McCormick, M., & Henderson, C. (2016). Gender discrimination in physics and astronomy: Graduate student experiences of sexism and gender microaggressions. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 12(2), 020119. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.12.020119

Berg, S. H. (2006). Everyday Sexism and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Women: A correlational study. Violence Against Women, 12(10), 970–988.

Blickenstaff, J. C. (2005). Women and science careers: leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gender and Education, 17(4), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250500145072

Correll, S. J. (2017). SWS 2016 Feminist Lecture: Reducing Gender Biases In Modern Workplaces: A Small Wins Approach to Organizational Change: Gender & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243217738518

Des Jardins, J. (2010). The Madame Curie Complex: The Hidden History of Women in Science. New York, NY: The Feminist Press at CUNY.

Ferber, A. L. (n.d.). The Culture of Privilege: Color-blindness, Postfeminism, and Christonormativity. Journal of Social Issues, 68(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01736.x

Ferrary, M. (2013). Femina Index: Betting on Gender Diversity is a Profitable SRI strategy. Corporate Finance Review, 4, 12–17.

Fleming, C. M. (2019). How to be Less Stupid About Race. New York, NY. Beacon Press.

Funk, C., & Parker, K. (2018, January 9). Women and Men in STEM Often at Odds Over Workplace Equity. Retrieved July 1, 2018, from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/01/09/women-and-men-in-stem-often-at-odds-over-workplace-equity/

Gay, R. (2017). Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Gordon, A. (2021). What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat. New York, NY. Beacon Press.

Hamad, R. (2020). White Tears/Brown Scars: How White Feminism Betrays Women of Color. Catapult.

Harding, S. (1986). The Science Question in Feminism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Jones, K. P., Arena, D. F., Nittrouer, C. L., Alonso, N. M., & Lindsey, A. P. (2017). Subtle Discrimination in the Workplace: A Vicious Cycle. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 10(01), 51–76.

Kitroeff, N., & Silver-Greenberg, J. (2018, June 15). Pregnancy Discrimination Is Rampant Inside America’s Biggest Companies. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/06/15/business/pregnancy-discrimination.html

Krivkovich, A., Robinson, K., Starikova, I., Valentino, R., & Yee, L. (2018). Women in the Workplace 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2018, from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/gender-equality/women-in-the-workplace-2017

Madsen, L. M., Holmegaard, H. T., & Ulriksen, L. (2015). Finding a way to belong: Negotiating gender at university STEM study programmes (p. 5). Presented at the NARST, Chicago. Retrieved from http://curis.ku.dk/ws/files/141015945/CurisVersion.pdf

Martell, R. F., Lane, D. M., & Emrich, C. (1996). Male-female differences: A computer simulation. American Psychologist, 51(2), 157–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.157

Orelus, P. W. (2013). The Institutional Cost of Being a Professor of Color: Unveiling Micro-Aggression, Racial [In]visibility, and Racial Profiling through the Lens of Critical Race Theory. Current Issues in Education, 16(2).

Perry, S. P., Murphy, M. C., & Dovidio, J. F. (2015). Modern prejudice: Subtle, but unconscious? The role of Bias Awareness in Whites’ perceptions of personal and others’ biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 61, 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.06.007

Shelton, J. N., & Stewart, R. E. (2004). Confronting Perpetrators of Prejudice: The Inhibitory Effects of Social Costs. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28(3), 215–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00138.x

Solorzano, D. G. (1998). Critical race theory, race and gender microaggressions, and the experience of Chicana and Chicano scholars. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(1), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/095183998236926

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. The American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271

Summers-Effler, E. (2002). The Micro Potential for Social Change: Emotion, Consciousness, and Social Movement Formation. Sociological Theory, 20(1), 41–60.

Sweet, P. L. (2019). The Sociology of Gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5), 851-875.

Uluo, I. (2017). So You Want to Talk About Race. Retrieved from https://www.sealpress.com/titles/ijeoma-oluo/so-you-want-to-talk-about-race/9781580056779/

Wemmers, J.-A. M. (2017). Victimology: A Canadian Perspective. University of Toronto Press.

West, L. (2017). Shrill. Hachette Books.

Wing, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal, Esquilin (2007). Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice. American Psychologist, 62, 4, 271-286

Yen, J., Durrheim, K., & Tafarodi, R. W. (2018). “I”m happy to own my implicit biases’: Public encounters with the implicit association test. The British Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12245

The Inconvenient Lonnie Johnson: Blues, Race, Identity

The Inconvenient Lonnie Johnson: Blues, Race, Identity

In a chapter titled “The Ethics of Doom Tourism”, Thomas explains that tourists might be drawn to vanishing destinations simply because of the label. In other words, people want to see glaciers, or the Great Barrier Reef, or the Amazon solely because of the endangered label. There is a school of thought which believes that this type of tourism will lend itself to tourist ambassadors, or people who return to speak of their experiences with the intent of changing humanity’s destructive patterns. Unfortunately, Thomas notes, it does not seem to be working (183). Instead, after a grand experience, people return to a regular life of consumption (for many reasons). This pattern, then, actually buys into and reinforces the doom narrative, rather than focusing on proactive measures toward change. Furthermore, many travelers have not been educated on the complex issues that affect such places, and likely do not understand the philosophy behind their actions. This is certainly true of myself.

In a chapter titled “The Ethics of Doom Tourism”, Thomas explains that tourists might be drawn to vanishing destinations simply because of the label. In other words, people want to see glaciers, or the Great Barrier Reef, or the Amazon solely because of the endangered label. There is a school of thought which believes that this type of tourism will lend itself to tourist ambassadors, or people who return to speak of their experiences with the intent of changing humanity’s destructive patterns. Unfortunately, Thomas notes, it does not seem to be working (183). Instead, after a grand experience, people return to a regular life of consumption (for many reasons). This pattern, then, actually buys into and reinforces the doom narrative, rather than focusing on proactive measures toward change. Furthermore, many travelers have not been educated on the complex issues that affect such places, and likely do not understand the philosophy behind their actions. This is certainly true of myself.

Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter

Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter The Railway Journey

The Railway Journey

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration

The Conjuror’s Bird

The Conjuror’s Bird

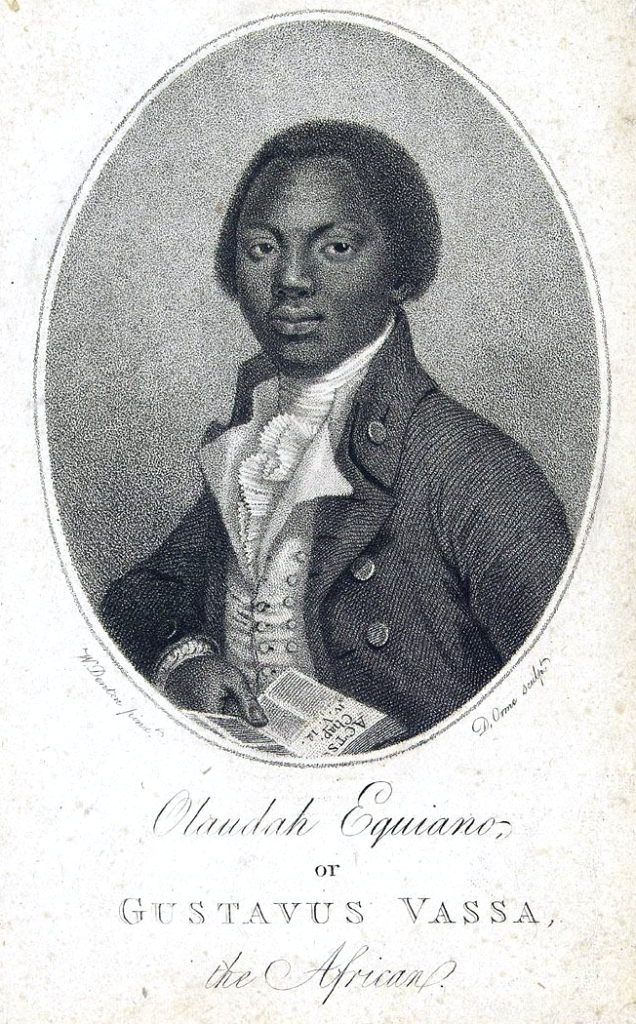

“The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or Gustavus Vasa, the African, written by Himself.” These tickets should be easy to sell, she thought. A story of life in Africa, kidnapping, enslavement, the Middle Passage. It’s eighteenth century HipHop. A man claims himself and defies the odds. It’s edgy; it’s truth revealed. Certainly the students who chose to go to a Historically Black College would be engaged, maybe even excited. Two young women arrive on time, one perpetually on her phone and the other hiding behind her computer. Thirty minutes into class, two young men come in, one completely empty handed, the other with a pencil and spiral notebook through which he shuffles trying to find a blank page. With ten minutes of class remaining, she gets their attention with the question, “How do we dehumanize people now?” She leads them by the nose, connecting the dots: slaves were dehumanized to legitimate atrocities against humanity; after 911, Muslims were dehumanized to increase fear and legitimate a war; Trump used tear gas on peaceful BLM protests for a photo-op at his convenience and a platform of “law and order.” How much has changed, she asks as she steps hopefully out onto her right pointe shoe, leg poised to elevate, but never coming off the floor.

“The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano; or Gustavus Vasa, the African, written by Himself.” These tickets should be easy to sell, she thought. A story of life in Africa, kidnapping, enslavement, the Middle Passage. It’s eighteenth century HipHop. A man claims himself and defies the odds. It’s edgy; it’s truth revealed. Certainly the students who chose to go to a Historically Black College would be engaged, maybe even excited. Two young women arrive on time, one perpetually on her phone and the other hiding behind her computer. Thirty minutes into class, two young men come in, one completely empty handed, the other with a pencil and spiral notebook through which he shuffles trying to find a blank page. With ten minutes of class remaining, she gets their attention with the question, “How do we dehumanize people now?” She leads them by the nose, connecting the dots: slaves were dehumanized to legitimate atrocities against humanity; after 911, Muslims were dehumanized to increase fear and legitimate a war; Trump used tear gas on peaceful BLM protests for a photo-op at his convenience and a platform of “law and order.” How much has changed, she asks as she steps hopefully out onto her right pointe shoe, leg poised to elevate, but never coming off the floor. Elizabeth Kuipers’s love of teaching began in

Elizabeth Kuipers’s love of teaching began in